The call came around five or six. It was my editor Joachim Buwembo. Whenever an editor begins their conversation with “ Where are you?”, the chances are they want you to abandon whatever you are doing for a story. As a reporter, especially a senior one, such a call often means you are being assigned a “big one”. That is because experienced journalists are like the knights on an editor’s chessboard.

When Buwembo called I was at Nando’s on Kampala Road. This coffee and pastry house had gentrified the street. My favorite spot was on the terrace by a wall almost the full height of a man that carved in a circular shape, almost like a shell, with the top touching the street above which connected Parliament Road to Kampala road. I would often sit to tables from the street side but behind the solid wall because it offered some protection – in case a car were to accidentally lose control and crash from the road into Nandos and it also afforded the best view. Besides, if one was coming from Parliament road and turning into Nandos, I would spot them first before I could be seen. I cannot recall who I was meeting when Buwembo called but his conspiring tone, slightly amused even, suggested something sinister was afoot.

“ Mayombo has been poisoned” he said. “ Is he dead?” I asked quite shocked at the news. Joachim’s source had not said if the ex-Chief of Military Intelligence, a towering political figure at the time, was dead or alive. He however asked me to treat the situation as if the soldier was dead. “ I need you to go and write an obituary” he said.

It just so happened that I liked to read Obituaries. Good obituaries were like miniature biographies, my favorite type of books. In fact, at the time one of my private pleasures was to bring copies of the Economist, Newsweek and Time, which The Monitor Publications distributed to Nandos and start reading them by looking up the remarkable lives of the departed. I was not ready to write Mayombo’s obituary yet and recognized that it was a big assignment. Nonetheless I rushed back to Namuwongo – where the Monitor Newspaper was housed, and where KFM, its radio had moved ( from a building across from Nandos called Crown House) and opened my computer to write a few lines.

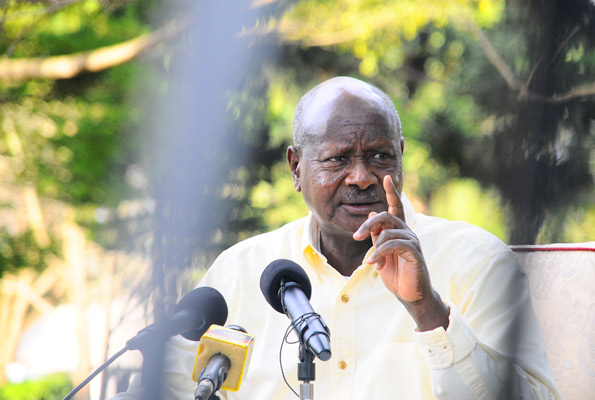

A few of the top brass were now aware that something really bad had happened to Noble Mayombo. Conrad Nkutu, our overall boss was Managing Director and, in his office,, I was summoned briefly. I had adopted a habit of taking a pen and paper to this office because Nkutu, who used to be a company secretary had a meticulous eye, troublingly better than most editors I had worked with, and behind it an aggressive and deliberate mind. He could give detailed instructions and then recall them like bullet points with precision later without having to refer to notes. Conrad demanded I show him a draft of my obituary – but rubbished it immediately with details about Noble Mayombo’s many lives, as a student activist, guerilla fighter, military and political figure who’s quick rise at the time was synonymous with pressure on President Yoweri Museveni to bring more younger members of his party and movement to the top management of the country.

Mayombo, one could say, was the poster child of what a succession, with young and competent juniors, may look like. So, the unfolding tragedy before us was almost as if the heir to the throne had been assassinated. Indeed, there were shadows everywhere. A dominant narrative was Mayombo’s supposed rivalry with John Patrick Amama Mbabazi which, the whisper campaign, insinuated was the man responsible – regardless of what had happened to the soldier.

There was another thread that had, not surprisingly, to do with Rwanda and Mayombo’s radicalism if not outright hostility to senior intelligence figures in Kigali. Having read some of the spymaster’s “intelligence reports” that had been leaked including one on Dr. Kizza Besigye and his alleged relationship with a rebel army in the DRC, the People’s Redemption Army – I knew enough to treat some of the rumors and talk with some skepticism. It was clear that Mayombo, his relationship with President Museveni, would attract powerful rivals. There could be no doubt about that. But whether any facts would support a cause of death related to these fights was always going to be hard.

Charles Mwanguhya who was one of the heads of the political desk, and who like Mayombo came from the Toro region joined the office at some point. By now, the silent beehive at Namuwongo had established that Mayombo was still alive. Charles confirmed from his sources that Mayombo was just over a mile away from the office at the International Hospital of Ian Clark. My draft obituary having been rubbished by Conrad and Andrew Mwenda, the news that Mayombo was not dead lifted the pressure to complete the copy. It had been an intense two or three hours and while my seniors demanded I keep working on it, I left the office in the company of Mwanguhya determined to go to IHK to see for ourselves how bad things really were.

And we did.

The drama with the death of Noble Mayombo – and his alleged poisoning returned to me this week with regard to something else. Noble Mayombo for all his polish was known to love his drink. The last time I recall seeing him was at the Sheraton Hotel. Mayombo had a boyish face and childish charm to go with it which gave him a kind of eternal youth. But on closer observation one could see that the slight yellow in his eyes, his drying lips and premature pot belly were down to his lifestyle around which were many stories in the newsroom. If he was suffering from liver disease and therefore was dealing with organ failure – it could be consistent with what we were witnessing.

Alcohol was more than a pet peeve of his boss President Museveni who, being a teetotaler, saw the drinking of alcohol if not a sign of gross indiscipline then as a serious character flaw.

I had heard about the president’s concerns with officers drinking not just with Mayombo but perhaps famously with his own brother Gen. Salim Saleh and another officer, Jet Mwebaze. It is clear with hindsight that as a military leader the president could have viewed alcohol as a direct threat to military discipline and operational effectiveness and linked it to other problems related to poor decision-making especially when the entire army ( and Ugandan society at large) was threatened by the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

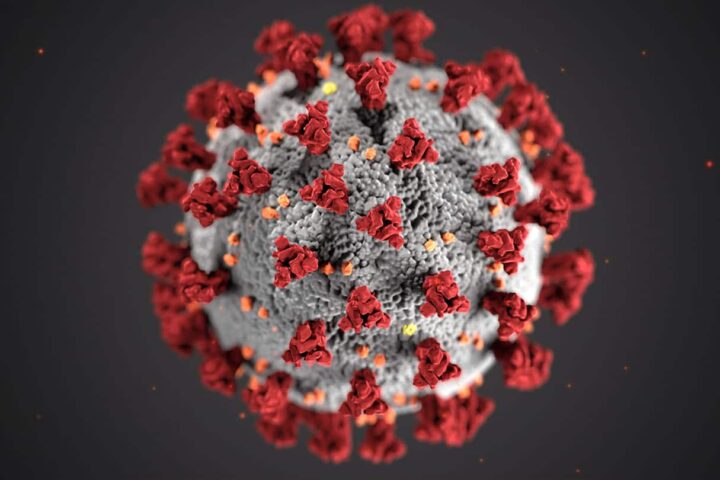

Mayombo and other officers were on the receiving end of harsh rebukes from their commander in chief over their drinking and did what they could to conceal it. Museveni also tirelessly preached against the dangers of drinking as he has in the past months with the lockdown restrictions under COVID19. It is not far-fetched to say that the continued closure of bars and other alcohol serving places is a moral war that he is waging in which he was suffered personal losses ( of officers and friends) despite not drinking himself.

But at what other costs when millions of lives and revenue depend on this very Ugandan of occupations?

TO BE CONTINUED