Note: Fast moving events have now thrust the question of violence, once again, at the fore of Ugandan politics. This article written in July ( so some references to the severity of the Coronavirus are dated) argues that the very act of choosing to go ahead with an election at the dawn of a frightening, death dealing pandemic is itself an act of gross violence. It chooses politics over life. That for most people should say everything about the stakes in Uganda. The rest, including the recent body count, is evidence of that choice.

(written for the Catholic publication – Leadership Magazine of the Comboni Missionaries)

JULY – 2020

Angelo Izama.

Uganda has planned to hold its general election in the early months of 2021 in what President Yoweri Museveni has dubbed “ scientific elections”. Like “scientific weddings” before them the reference is to proposals to meet the demands of democracy and the constitution by conducting a poll in conditions with minimal interactions between voters and candidates.

Under ordinary circumstances, sans the COVID-19 virus, the election period would be defined by a countrywide program of meet and greet. Candidates would hop on the stump, prioritizing home visits, Church and Mosque appearances as well as funerals, birthdays and virtually every calendar entry that promises a congregation would be filled by candidates or their supporters.

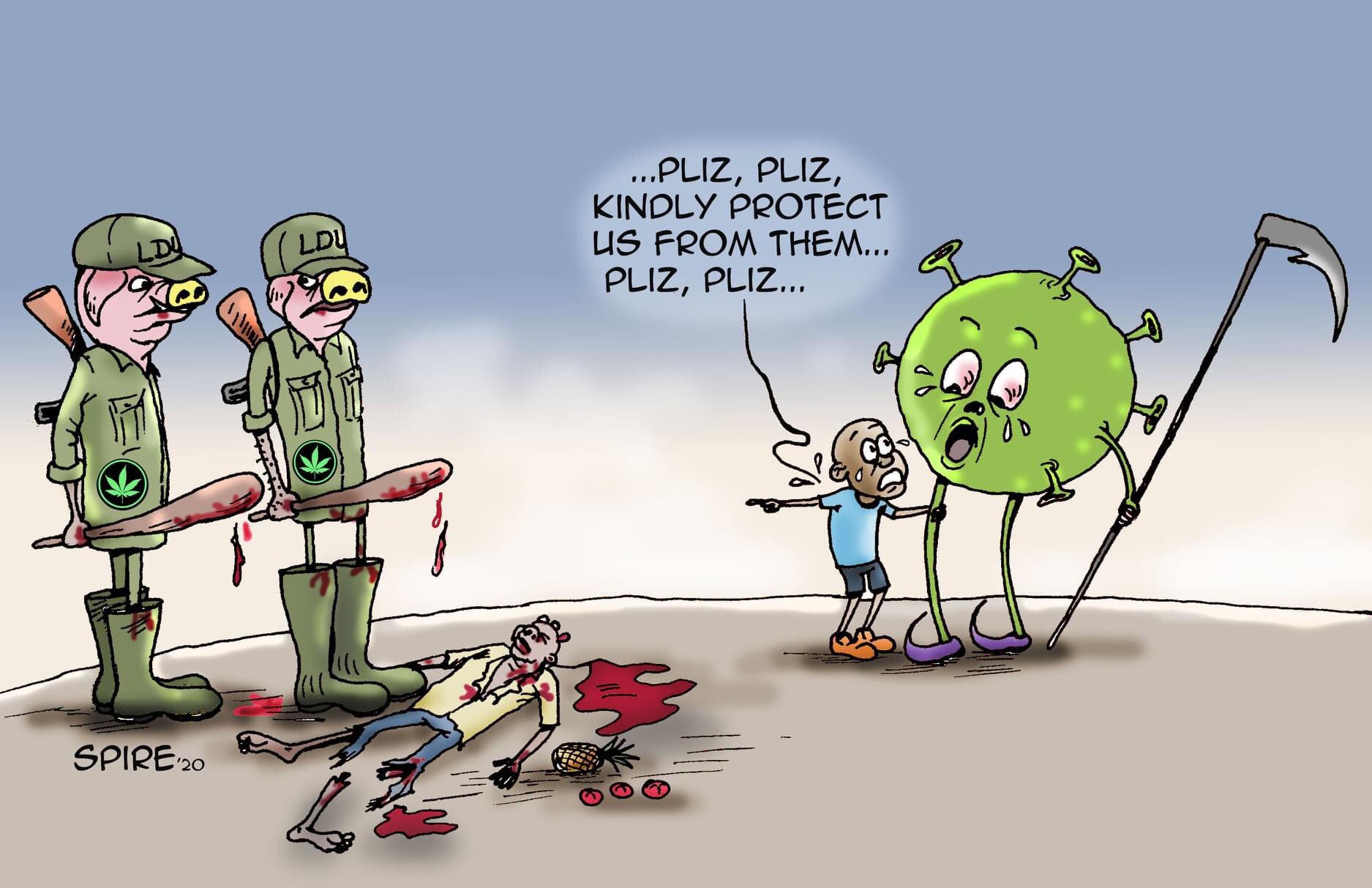

As any visitor to Uganda around election time would have noticed, the soundtrack of the elections especially at its peak in the countryside is a sort of extended carnival with parties, drink and excitement. In the last decade elections have also been conducted under the closer watch of the police and army. The political parties have not surprisingly taken issue with the new guidelines for the “scientific election”. Muscular enforcement of the lockdown conditions – seen as excluding ruling party candidates trying to reach their voters did not help. Besides disrupting their political plans and the culture of conducting campaigns, the emphasis on digital outreach for campaigns and mobilization have caused considerable angst amongst all – opposition and mainstream.

This is because replacing the contact sport of retail politics during the high political season with a virtual one places new demands on candidates, parties and supporters. It has created two tensions worth examining closely. The first is whether technology can, within the meaning of democracy and electoralism, deliver a meaningful election. If it cannot what adjustments need to be made before polling day that satisfy all sides. The second tension is the political economy of a virtual election – namely that virtual campaigns regardless are still Ugandan, and because they are Ugandan, are about the political issues of the times.

This includes Uganda’s severe form of presidentialism. The main prize in the election is Executive power and the holder of that power is running for a sixth term in office. However there is also the thriving market for municipal and legislative posts that draw the most interest and is the dynamo driving the democratic vehicle. Both, Executive Power and the parliamentary jamboree are dominated by the election winning machine of the National Resistance Movement, the ruling party which is a behemoth of the political culture itself and whose support for the “scientific election” has made it inevitable despite objections from some quarters.

Corona colonised

A third factor, which should be the most important is the coronavirus itself. It is the virus to which we owe the health logic for the digitally infused election. However in some respects the virus is the least relevant. With zero deaths and slightly over 1000 official cases ( at the writing of this article) Uganda is not the epicenter of the COVID19 pandemic. If anything, going by the global footprint of COVID19, it is instead one of the sunnier spots. After months of the initial lockdown forbade public transportation and normal trade and commerce, the social controls imposed by the government, that have had a high degree of public support, have begun to wane.

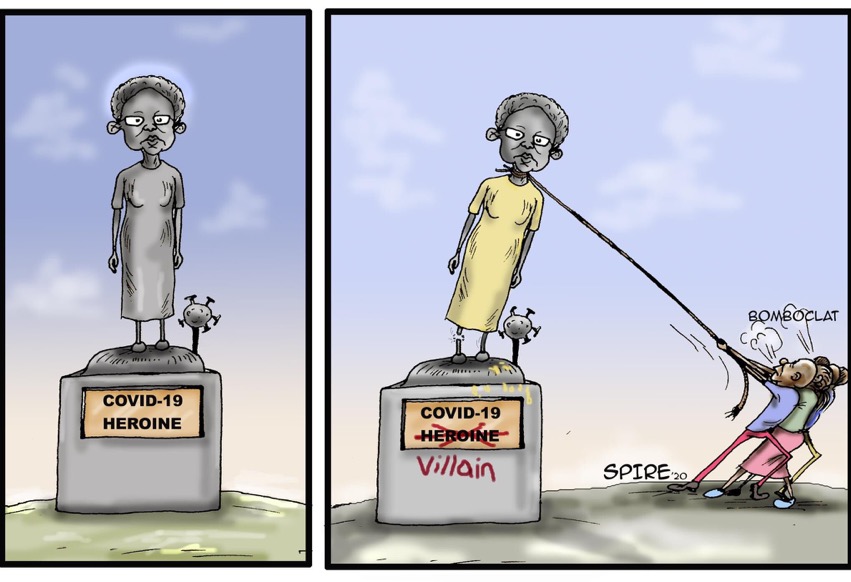

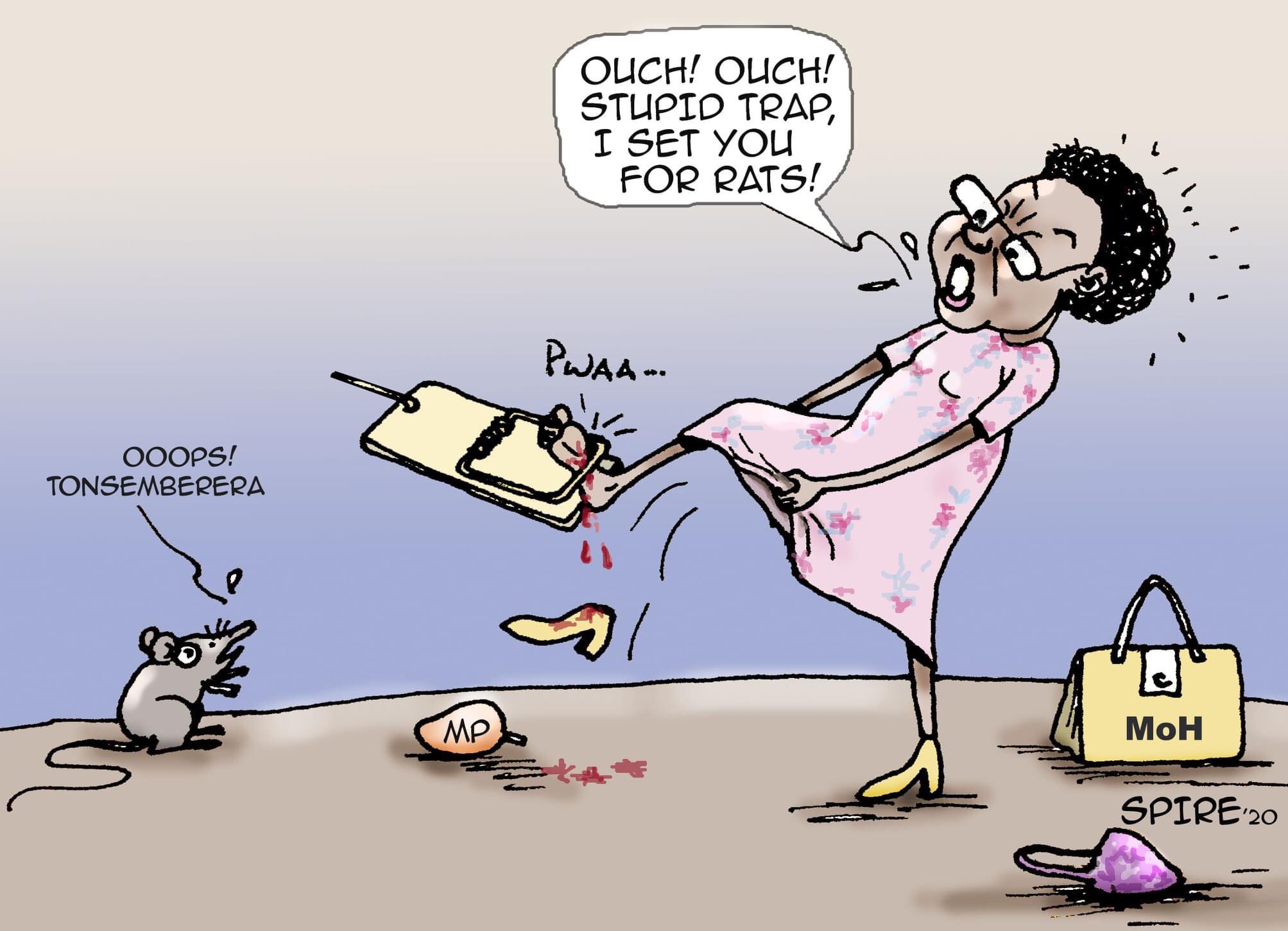

So much so that as the election season begun in earnest, with a scientific poll in the foreground, the health minister Dr. Ruth Aceng supplied the symbolism that best characterizes the portion of “science” that comprises concern for COVID-19 in the context of elections. A technocrat, and the face of the Uganda national COVID-19 response Dr. Aceng announced she would run for the Lira District Woman Member of Parliament. She was on Friday 10, July 2020 pictured mobbed by crowds in Aromo sub-county without a mask and not maintaining social distance. In a statement she issued after the incident Ms Aceng said she was “not holding a political rally” but was actually involved in a mask distribution exercise.

The spectre of “Mama Corona”, as she is known, now a candidate for office disregarding the rules on social distancing for political advantage drives home the thin relationship between the health science and the logic of digital elections and expounds in dramatic fashion- the “political science” involved.

It was clear that the political class ( and civil society) would respond by simply ignoring the rules like Aceng but also others like Ephraim Kamuntu in Sheema who was recorded holding a political meeting in a church or they would threw the legal rule book at it to neuter its impact.

In Parliament, for example, Wilfred Niwagaba (Ndorwa East) said the guidelines were impractical and likely to be dis-regarded as they were based on statutory instruments and not a new law designed to take into account the unique situation created by COVID-19.

“The justice minister is quoting guidelines passed by the Ministry of Health on Covid-19. How can statutory instruments passed under a delegated authority usurp the Acts of Parliament?” he wondered. His argument is that elections are sanctified in the Constitution and Electoral laws that cannot be set aside by weaker laws reflect a widely held view amongst the opposition that President YK Museveni should have declared a State of Emergency in the first place in order to run the country under special conditions not just via regulations. But in truth – this view of a state of emergency did not gain traction because opposition politicians, including presidential candidates amongst, them are concerned that the restrictions around interaction between the candidates and their supporters will ultimately undermine the result – that is the vote declaration process itself. It had little to do with the coronavirus.

“We have been accompanying our results from polling station to the district to avoid theft, but now that a curfew starts at 7.00pm these elections cannot be followed. Is that a free and fair election?” said Merdard Ssegona (DP, Busiro East). In strictly legal terms of course Uganda has not really held any free and fair election – rather, according to the courts, elections that reflect the broad will of the people, on a balance of probabilities. The curfew was modified but the concern over stolen elections and election malpractice is widespread and one of the most litigated aspects of the process. The question then of how a digital election contributes to the democratic spirit and function without free movement, interaction between candidates and voters ( as provided by various laws), in conditions where politicians are likely not to comply extends to practical questions on how these guidelines will be reflect on the political culture.

Who will abide by the rules of meetings of 50 people while indoors ( in a space of 100 meters), 200 people outdoors and outreach primarily by digital means? Also in a country obsessed about the control of crowds for fear of the “vote of the streets” and popular uprisings, is the scientific elections not in reality the digital version of the controversial Public Order and Management Act ( which outlaws gatherings and has been the bane of opposition rallies before COVID-19?)

How will the large body of candidates especially in the MP race, the prize for most contestants ( 1300 persons contested in the last election for the 400 or so seats in the House, a number that could well double in 2021) share the available digital space especially radio and TV time? Opposition voices point out that nearly 80% of radio stations are owned by the NRM party supporters and functionaries with a long history of denying access to their opponents and accuse the Uganda Communications Commission itself of bias ( under UCC regulations imposed by the Ministry of ICT while it was run by one time minister for the Presidency Frank Tumwebaze – the president has the nuclear option of legally switching off the internet in an emergency).

ALL OR NOTHING POLITICS

If the terrain is unfair and made even more politically more febrile by the COVID-19 conditions how can an election, scientific or not, ever be considered as free and fair. The answer could be that the political culture has internalized elections as simply not being about fairness but rather competition – where the rules are fungible and where advantage lies in working around the conditions dictated by power.

The “scientific election” is a triumph of politics and of politicians over everything else.

Even for the opposition – change under less than ideal conditions is the hope that holds together their participation even as they object the unfairness of the rules. After all Lazarus rose in Malawi and in Kenya, David slew the election. These are two cases were elections were annulled because the rules were successfully challenged in the courts of law leading to the ascent of Lazurus Chakwera in Malawi and shaking up Kenyan politics permanently with a re-run. So how far can Uganda be?

If choosing a general election over the general wellbeing of citizens occasioned by a complex and unpredictable pandemic can be packaged into the law of man versus the law of nature – then nature has lost. The law of man, that man-made constitution, animated by political activity, of loud legislatures, opinions upon opinions, statutes and batons, guns and bayonets, taxes and prisons and often death stood no chance against a global pandemic caused by the SARS-Cov-2 virus also known as the coronavirus.

The “science” cannot explain Uganda’s exceptionalism or that of African countries in general, which outside of South Africa, have had a low casualty rate. There is no solid scientific basis to support a view that there would not be a great reversal of fortunes in the African story with deaths happening later. Just like there has been none to explain why mortuaries are not filling up with the dead now. Weighing all of this, the choice is stark; dead people cannot vote.

There is an ethical as well as practical matter here. Should Uganda hold a constitutionally scheduled election, be it under managed conditions as is proposed, or postpone it all together until the science can offer answers that can protect everyone? On a forked path that is the year 2020, Ugandan leaders have opted for elections with a few – mildly scientific caveats. This is possible because such is the appeal of politics to the elite that the political show must go on regardless.

Leadership Magazine

[…] https://angeloizama.com/dead-people-cant-vote-on-the-essential-violence-of-the-uganda-election-of-202… […]