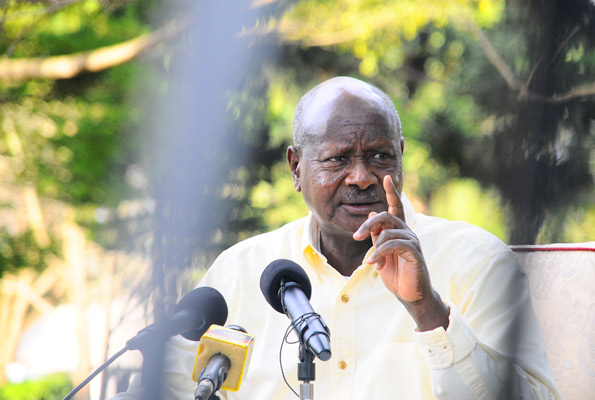

Late Friday afternoon Ugandan Mps voted on a margin of 149-39 to pass the Petroleum Exploration and Production Bill 2012. Once it is signed into law by President Yoweri Museveni it shall constitute the primary law for governing Uganda’s promising oil sector. Two other bills, a midstream and downstream bill remain. The last , on revenue management, promises the fireworks that have accompanied the passing of this one. The Friday vote reminds one of how healthy a discussion for the Ugandan Parliament -electronic voting will be. Nonetheless one lesson to take away from the Petroleum Bill is that it was more serious outside than inside. It is one of the most negotiated pieces of legislation in recent history. Its fate was determined by nearly 8 caucuses of the ruling party , tons of phone calls many made by or on behalf of President Yoweri Museveni ( pictured) to rally the troops , a failed parliamentary coup that could have left it without a Speaker, what could have been a constitutional crisis and an unprecedented use of the media by both those in support of and opposed to the bill- to mobilize sympathy for their positions.

This episode of political gymnastics has been as polarizing if not more than the decision in 2005 to lift Presidential Term Limits. The lawmaking process has also shown what is possible when well-financed civil society groups team up with motivated lawmakers.

It also poses a rather ironic question. Prior to this level of public engagement Uganda had an increasingly strong negotiating position vis a vis the oil companies and other actors. Most famously was the decision taken by the Executive on the so-called stabilization or protection clauses- mainly without the help of parliament. The standoff over clause 9 which produced the dramatic results of Friday afternoon was about the power of the executive. Its important to note that by contrast executive actions in the oil sector have been strong in the public interest. However they contrast weakly with the record of the government on public trust especially in the shadow of public scandals that have accompanied the lawmaking process for the oil bill like flies buzzing around to signal decay and infestation.

Now that the law has passed the next series of actions will focus on the inauguration of the institutions it will create and the lifting of an unofficial freeze on new licenses for oil exploration.There are many implications of this law that we shall track closely on this blog.

For now let me endeavor to make some broad arguments.

My primary approach to the subject of oil in Uganda, and by extension a number of African and other countries that will discover oil or mineral wealth at this time is that their path will be affected by the kind of political institutions in place. In particular I speculate about the impact of democratic institutions and democratic political culture on countries that have recently encountered commercially viable natural resources.

By this I mean the presence of such institutions such as a parliament, a relatively free media and judiciary and an interested public. Over the next year, and as a series of researched articles I intend to publish I will not simply argue the potential of democratic institutions and culture, if present at the onset of a country’s natural resource path, to significantly alter the experience of such a country in the non-traditional sense we have come to expect, that is that they would be “resource cursed”, but I would further suggest that if indeed, democratic institutions and culture are responsible in a credible way for modifying the behavior of the oil/gas and mineral industry in countries with newly discovered natural resources, then it represents an unprecedented opportunity to re-imagine the future of Africa with abundant natural resources.

And this would be true also for countries such as Nigeria, Equatorial Guinea, Angola or Sudan that were undemocratic when they became oil producers. It is very possible and I assert it here that the presence of certain democratic political institutions will change the way these countries navigate the future of their oil and gas sectors.

Some may say this is reading to fast and too early from the Ugandan experience but only perhaps. Naturally others will claim it is not an argument one can export.

After all what I am suggesting may be rather obvious; that democratic institutions such as an independent judiciary, effective legislature and an accountable government that can be peacefully changed in an election, do not just define a highly evolved political system but also a progressive business environment. Their absence or presence therefore present different opportunities for extractive industries infant or mature.

Indeed by contrast the curse of plenty or the oil curse in post independent Africa occurred in countries with closed political systems, under military dictatorships or extended one party rule, in situations of civil war and political volatility. These conditions provided evidence that multinational corporations including International Oil Companies operating in such an environment behaved as atrociously ( like Shell in Nigeria or Exxon-Mobil in Indonesia) as the governments they partnered with.

Uganda represents a unique opportunity to observe how the transition to democratic forms of government affects a country’s choices in the oil and gas sector but also how a fragile and emerging democracy is affected by the prospect of new resources from oil.

At close quarters it is also revealing of the behavior of the political elite, the posture of oil companies, and the influence of public opinion and media. The same lessons I argue can be applied to countries who while carrying the burden of the oil curse are also experimenting with hitherto weak or absent democratic political institutions. Over to you.