Somewhere in my collection of odd papers, reports, tips from sources over the years are the incorporation papers of Uganda Taxi Operators and Drivers Association (UTODA). As a private company UTODApulled off a masquerade of a “public service” or even official government agency and must be congratulated for the feat. Most people did not know or assumed that UTODA was a government mandated service and mistook its “self-regulation” as a body of rules resident in some law somewhere beyond the Companies Act. In only rare episodes has public transportation in Uganda come to a complete stop. UTODA’s success is indeed a lesson on the contours of policy making in country’s like Uganda or rather the political economy of this subject.

It certainly appears as if the National Resistance Movement waited until the transport sector is maturing to seek to administer it directly. Before then UTODA appears to have acted as its proxy in return for some have suggested for political support. The outsourcing of parts of public transport UTODA controlled was just part of the story however.

If you imagine security and public transport as government mandated services, UTODA is the equivalent of if the Uganda police were a largely private security outfit – like KK Security or Pinacle ( one must say though that security for residences and businesses is mostly paid for by individuals and at about 30,000 men and women, private security is indeed a huge ‘subsidy” that the government enjoys or a service that has also been privatized and outsourced).

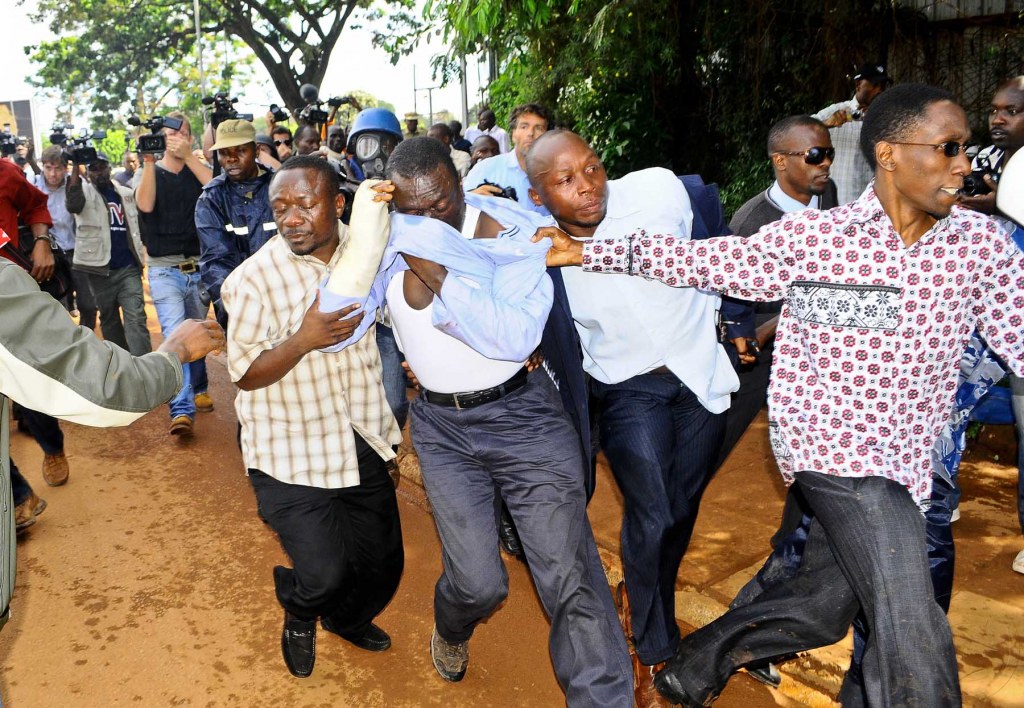

Yes there has been the occasional strike when UTODA pulled rank over its political backers on issues like fuel prices or fare rises but overall the underwhelming-ly average quality of its service continued uninterrupted. As the company is being edged out of its main business – collecting dues from taxi drivers and owners – many wonder rightly what the future of public transport itself will be and what new deal the NRM will cut with the city’s poor.

UTODA’s constituency being largely poor, urban young men (originally ganda and predominantly Muslim) was its genius and crucial bargaining chip. Perhaps the height of UTODA’s double identity as a business and quasi-political organization came in 2007 when during the Commonwealth Summit its members doubled as volunteer securitymilitia. The company offered this extra service to the state.

Specially trained “commandos” would man parks and travel in taxi’s to watch over passengers and intervene in case of trouble. This the main investment in security was eyes and ears- UTODA became a mainstay of the security plan for Commonwealth delegates.

I had dinner with a senior member of the President Yoweri Museveni’s staff as part of the investigation into UTODA at one of Kampala’s upscale restaurants earlier that year; itself a sign of how high the group’s influence spread.

“ Some of our members have long protected UTODA as a bargain struck during the initial takeover of Kampala when Baganda Muslims asked to be allowed to handle transport” said my source, a well-heeled politico who like successful NRM cadres owned property including interests in the transport sector.

He explained that their Baganda/Muslim lobby argued that their group were “not educated” and could therefore compete in the new political dispensation like other participants in NRM’s triumph. This was accepted, the source said, and the political bargain continued to have currency for a long time.

If this was true what became of UTODA over time was not just a source of employment for a growing urban underclass. The identity of poor urban youth has changed across time but the company was a cash cow for those who made and supported the bargain that kept the company in business. One of the figures rumors associate with UTODA’s political support is NRM Vice Chair Al Haj Moses Kigongo, for example, a wealthy businessman in his own right whose wife Olive Kigongo is the long reigning head of the Uganda Chamber of Commerce.

At its height UTODA controlled billions in revenue and paid a fraction in official taxes. It managed to get away with it by leveraging its political muscle in its agreements with the Kampala City Council (which is now Kampala Capital City Authority) which while run initially by what UTODA’s NRM friends considered “ oppositionist” forces ( Democratic Party but Buganda networks) was empathetic to UTODA. In any event the City Council was a hotbed of corruption itself. One of the most memorable stories of my career was on graft in the city and how government loans and grants would simply disappear into the bellies of its fat cats. KCC graft

That government officials, city officials, ministers, clerks and everyone in between was on the take had long been alleged but the network was never clear and perhaps a failure for the journalism that failed to unveil it.

That government officials, city officials, ministers, clerks and everyone in between was on the take had long been alleged but the network was never clear and perhaps a failure for the journalism that failed to unveil it.

To its credit while UTODA remained a huge tax evasion exercise it never descended to criminal depths like similar networks elsewhere on the continent. In nearby Kenya, the capture of public transportation by “tribal” militia like Munguki and other criminal networks created a violent mafia economy,which became a major liability during the political transition crisis there. Mugiki and associated groups too had political connections but appeared at points to direct itself. UTODA’s passivity in contrast is evidence of the nature of its relationship to politics and government. This bears comment. At points when Uganda faced urban terrorism, security agencies were able to draw from its reach amongst specific communities. Despite the lack of regulation of the transport sector and the vast enterprise that UTODA controlled Kampala maintained a reputation as a largely safe city. This even if the potential has existed for criminal networks to thrive – like in 2002 when violent robberies of forex bureaus and banks and car theft threatened to bring the city to its knees. Such This relationship is now at risk with the shifting tide of city politics and its something to keep in mind.

However this arrangement had its limits set. As the demands on public transport grew so did UTODA’s value proposition. And when the government sought to reform the city administration it seemed UTODA’s days were numbered.

First to ebb away was its influence. I always felt that since entry and exit into the taxi business was pretty free that UTODA could not control its “members” for long. As the axis of ownership diversified from the initial base- as did the political argument. Some its most vocal critics have been internal and it was over UTODA’s management style and not its political bargain. This is a sensitive subject because of the tribalism at the center of the transport business so we will leave it at that.

As KCCA takes over UTODA as a public transportation issue remains a major policy challenge. To approach the transport business simply as a source of city funds is very narrow and will likely lead to friction. Transport as a service needs radical reform and that is what UTODA pushed back for years. KCCA needs to return focus on regulation and enforce its charter by investing in rules that direct private investment in the transport sector in ways that rationalize and regularize the transport experience. If KCCA ( run by Jennifer Musisi above) remains a collector of fees it is also at the risk of political capture though some would argue that this has already happened.

At stake is not just the predictability of fares, routes, health services like toilets etc but also the exit of taxi’s and return of bus transport to Kampala. Eventually boda bodas and their associations will pose a similar challenge but the UTODA experience should show that reform may take time but it’s not impossible.

Here is my 2007 story on the UTODA mystery. UTODA