Original was posted here on the ACME website

From Song of Lawino

And while those inside

East thick honey

And ghee and butter,Those in the countryside

Die with the smell

They re-eat the bones

That were thrown away

For the dogs.

And those who have

Fallen into things

Throw themselves into soft beds,

But the hip bones of the voters

Grow painful

Sleeping on the same earth

They slept before Uhuru.

…

If only parties

Would fight poverty

With the fury

With which they fight each other

If diseases and ignorance

Were assaulted

With the deadly vengeance

With which Ocol assaults his mothers son.

The enemies would be reduced by now.

– Okot p’ Bitek, 1972

The 2011 issue of the literary magazine, The Transition, founded in Kampala in the 1960s, run a ‘Uganda’ issue that included an article with the evocative title “Season of Dissent”.

On the streets of the capital where the founding editor, Rajat Neogy (R.I.P) had sought to understand the centrifugal forces shaping Uganda’s, and therefore Africa’s democratic future, familiar scenes of brutal repression – police with teargas and batons, live bullets and disappearances – were being played out. Then, as now, Uganda was caught in the headwinds of the desire for change and by the inability (or perhaps the unwillingness) of such change to be negotiated peacefully, civilly and without bloodshed.

On the streets of the capital where the founding editor, Rajat Neogy (R.I.P) had sought to understand the centrifugal forces shaping Uganda’s, and therefore Africa’s democratic future, familiar scenes of brutal repression – police with teargas and batons, live bullets and disappearances – were being played out. Then, as now, Uganda was caught in the headwinds of the desire for change and by the inability (or perhaps the unwillingness) of such change to be negotiated peacefully, civilly and without bloodshed.

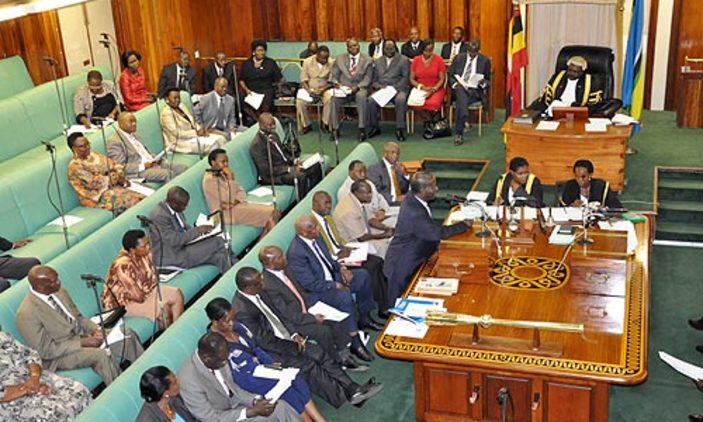

During the week that the Public Order Management Bill was passed, the media also carried continuous coverage of the elections in Zimbabwe where a revolutionary grandfather Robert Mugabe sought to stay in office. In Cairo, scenes of street protests that deposed a democratically elected President. In Uganda the news was full of images of rowdy members of the almost 400-strong parliament debating the merits of criminalizing dissent.

Dramatic episodes like this are history relived. Where political consensus has stymied in the past – such as was the case in the promising opening of independence – political competition between power holders and their challengers become a dual race. On the one hand they monopolize the instruments of repression and on the other, justify or legitimize it.

When Apollo Milton Obote faced a consensus undone in the late 60s (one that ended with the jailing and subsequent exile of Neogy) he passed emergency legislation using his party’s superior numbers. Of these was the similarly named Public Order and Security Act of 1967. A few short years later the consensus fell apart. Shortly thereafter, following a coup that made Uganda famous by thrusting into the spotlight the military government of Gen Idi Amin Dada, the new president put to paper as his 18 reasons for taking over the government from Obote.

Today, Amin’s rationale reads like it could have been drafted by the current political opposition.

Reason No. 1 was the “The unwarranted detention without trial and for long periods of a large number of people, many of whom are totally innocent of any charges.” No. 3 outlined poignantly “The lack of freedom in airing of different views on political and social matters.”

Maybe after the 2011 parliamentary debates on oil governance some may find it cynical that in 1971, the man dubbed the “butcher of Africa” wrote as his reason No.6 for grabbing power “Widespread corruption in high places, especially among ministers and top civil servants has left people with very little confidence, if any, in the government. Most ministers own fleets of cars or buses, many big houses, and sometimes even airplanes.” A full list including crime, economic inclusion and social justice can be found in The Report into the Commission of Inquiry into the Violation of Human Rights that was prepared under Justice A.H.O Oder, established after 1986 to investigate Uganda’s perennial crises and its human cost.

It does appear, then and now, that the issues for governance are consistent where political disagreement is rife and power believes it faces eminent threat.

The concept of dissent as recorded in the past, and now an Act of the 9th parliament, is condemned essentially as a tool of regime change, not as a right of citizens or an essential part of the democratic architecture. Indeed for the ruling establishment of the National Resistance Movement, whose ideas of change and revolution were birthed in post-independence Africa of The Transition’s early years, the type of protest movement is the militant tool-kit of radical change that today’s allegedly western backed democracy promoters unleash that acts first as a way of paralyzing government and stopping it from “delivering services”.

The language of maintaining order is aligned to the rise of the security state to defend its right to govern by force if necessary, but more desirably by force that is clothed in political consensus and law. It is also a language of resistance against political interference from sinister “external forces” like the ones that toppled the Mubarak and Ben Ali regimes.

But regardless of fears of those in power the real questions about a law as restrictive as was passed will not simply be about political competition or the outcomes of the epic ideological wars of East versus West. The reckoning of law that criminalizes dissent is a lot more insidious because the right to object is in many ways a definition of freedom. It also has little to do, in all seriousness, with the administration of public goods, the assault on “ignorance and disease”

How did our rights, to assemble, to speak our minds and in doing so, participate as citizens become entangled in such a law as the Public Order Management Act? What is in this case then for the future of dissent? These are the big questions of the before and the after. Today appears to be another watershed moment where political competition or more aptly the competition for power is overriding the institutions that protect the right to disagree as a crucial part of the democratic experience. They also threaten, by doing so, the peace.

Democracy is founded on dissent, on the right of refusal, on conscientious objections and where this is not possible, on protest. Where these protests are the majority, on the inevitability of change. The system of elections itself is grounded on dissent: the status quo, represented by the government of the day, its ideas and policies, are put to the test at the ballot regularly. In reaching out to change the hearts and minds of voters or to maintain their confidence, competing political voices mobilize dissent, distinguishing themselves from their opponents by calling on their supporters to object, to reject and to persuade others as well to jettison the views of their opponents.

Dissent is not about the lack of control of the state, but freedom of choice. Good government is eventually seen by its ability to tolerate and organize around dissent. Those who see the current steady erosion of the freedom to disagree worry that when finally in a few years, a ballot is held in 2016, the conditions to disagree will no longer reflect the capacity of people to do so freely. Therein is the danger of the Public Order and Management Act.

***

Angelo Izama is a Ugandan journalist, writer, analyst and OSI fellow researching the political economy of Uganda’s oil sector. For more information visit www.angeloizama.com

For further reading on the debate of the Public Order Management Act:

- Daily Monitor ‘Parliament passes the Public Order Management Bill’

- The Observer ‘Public Order Management Bill: Whose interests do MPs serve?‘

- Amnesty International ‘Public Order Management Bill is a serious blow to open political debate’