The dry season in Moyo, in West Nile, Uganda can be scotching. When I was growing up during the monsoon, winds that arrive here having crossed the dessert overnight through the leafy parts of South Sudan and over the mountain range that separates the two countries camp in wintry conditions at the town. It was not unusual to find morning fires were children and teenagers sat as women prepared breakfast. But this only lasted until after 9. From then the weather suddenly develops a temper and by midday tree shades become small varsities where folks gather, some to do their chores, to apprentice or to drink and converse. Right across the street at Onama Road where we lived (named after the late Defense Minister Felix Onama who served during Idi Amin’s government) in an extended compound of relatives, was a clay pot at the house of one of my aunts.

It happened to be one of those clay pots whose drink was so fresh, earthy and wholesome, that after the midday meal, I liked to stop ,as if by accident, for a cup. I was not alone. The information economy in the village like any small place was near perfect. Many children and adults knew about Mary’s pot and her hospitality. In fact one was required to offer information. A strong rebuke would await some wayward child who forgetting he had not saluted an elderly person in the morning would find a case lodged against him in the evening after school. People went by first names and the names of their families.

This was Uganda however in 1985. Today where dogs also went by a first name , the bulge in the country’s population over the last two and a half decades has left its mark, on the weather, the land and the people. Moyo is still a sleepy town by Uganda’s standards. Nearby towns like Gulu are edging towards cities.

Everywhere however the crowding has brought with it new challenges. A story in the Daily Monitor, Uganda’s main independent paper (where I work) brought this home the other day. Just weeks before a new Minister of Health was appointed, the paper reported that Moyo Town had just received this May its long awaited batch of rabies vaccines. The town had been on hold since 2007. The new Minister of Health Adroa Christine incidentally went to Moyo Senior Secondary School, my Alma meter, which seats at the edge of the old town right next to Moyo Hospital.

Permit me to do some argumentation here. My view of Uganda’s problems if one can generalize such a thing is that it involves two issues. One is of internal asymmetries and the other of external ones. Presently I see these distortions of information as essentially a primary challenge.

For example, the Ministry of Health in Uganda does not have information on the exact number of health centers in the country according to the National Medical Stores that delivers drugs on behalf of the government. In fact despite being hailed for its reforms in the 90’s, one will be hard pressed to find a known estimate of aids patients or any other inventory essential to understanding how to plan healthcare or even postal services.

Fixing this information economy has not been a priority for the government.

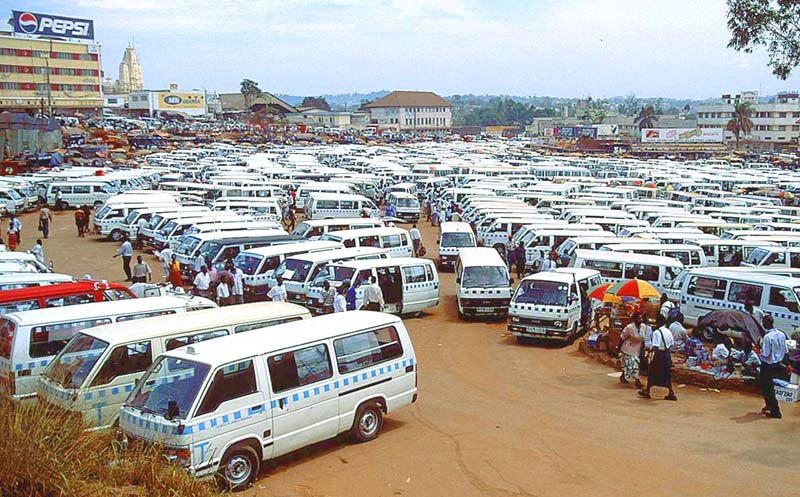

It’s only this year that a National ID project was launched. If one does not know the number of people in a country, clearly the number of virus bearing dogs is a distant target. So bad is this condition that banks can’t lend cheaply (no credit reference bureau worth talking about, interest rates are prohibitive at 27%), police can’t track criminals (no criminal data base, hell we don’t even no the actual number of policemen) and when politicians come to office, Ugandans are accustomed to finding out that they slipped through many legal filters to arrive as flukes with academic achievements conjured from the main street of forgeries, Nkurumah Road (no pun intended to Ghana’s founding father) in Kampala. There are just over a million bank accounts in a country of 32 million where some 11 million people carry mobile phones.

The informal economy is far larger than the formal one. Judging by the number of contributors to the only provident fund (just above 500,000) formal sector workers are less than 0.5% of the economy. There are attempts to cope with this pace of change that are worth mentioning. Many more Uganda’s rely on mobile money transfers today that either banks become phone companies or phone companies acquire banking licenses. Land title records are only beginning to be stored in an electronic database. A lot more can be said about this chaos and indeed we will here.

Add to this Uganda’s huge bailout by international aid and you realize why we are in such a fix. Aid dollars do not fix roads, post offices, electricity grids or other essential infrastructure for a working state. Instead aid money as far as I can see tries to conduct relief within these conditions. The cost of aid is high for aid dependant countries because aid procrastinates on investment infrastructure because of its ability to work within these challenges. Perhaps the best example of how ingrained this mentality is can be seen from the pronouncement a couple of years ago by Uganda’s outgoing Prime Minister, a former head of Makerere University Professor Apollo Nsibambi. In 2005 when Uganda’s roads were falling apart he announced that the cabinet would upgrade to land cruisers, because the roads were so bad. Landcruisers are the preferred car for aid workers too. A study of the government vehicle fleet should the government was spending some 54 billion shillings on fuel and maintenance of its luxury fleet and guess what- the biggest fleet (11,000 cars or over 30% of the fleet) were operated by the Ministry of Health. If Moyo in these conditions has to wait years to receive a rabies vaccine then one can see the extent of the dilemma.

Before we pose another question consider this about health care expenditure in Uganda. Over 80% of healthcare dollars are provided by donors however with less control over donor agendas than is admitted- almost all donor funds are dedicated to just three or four programs ( HIV/AIDs, Malaria, Tuberculosis mainly). It has very little correlation to Uganda’s disease burden let alone the clinical needs of most outpatients. What is worse, this information is not available to the government and does not form part of its planning matrix.

These distortions however present the following problems with aid and investment. Firstly, that aid has been a great procrastinator of investment. In the mid 2000’s my colleague Andrew Mwenda begun theorizing as to why aid has been a disaster for Africa.

A book “Dead Aid” by Dambisa Moyo ( above but no relation to Moyo town) has been written. I have not read Dambisa’s book but I think she and Mwenda has posed an important but ultimately wrong question. My question would be not why aid has not succeeded or why aid has failed but why investment has not happened? At its core the external asymmetries we should return to next have to do with the aid story becoming the only story in Africa to the extent that so much intellectual energy and ink has been used to explain the fate of aid. Aid has become dogma and draws its fair share of abolitionists.

However aid does graver damage. It negates investment. If instead of building roads governments and their “donor partners” are coping with potholes using high-end Japanese vehicles we have ourselves a one problem. The cost of delivering aid and its efficiencies are one issue to tackle, the other is to look at this number as the opportunity cost of investment.

Millions of companies around the world cannot come to invest – not just because they are no proper roads or basic infrastructure but also because Africa has been curved out for aid the way Asia is for investment. The whole philosophy is wrong so much I no longer tune in to G8 meetings or their cousins, which raise money for “ development aid” or have cast the work Multinationals in Africa as mainly Corporate Social Responsibility (the language of aid/charity of private companies).