Hail, Emperor Kaguta

By Izama Angelo Feb 28, 2005

At the height of his reign, the most venerated Emperor of Ethiopia, the King of Kings, the Lion of Judah, his Royal Highness Haile Selassie was the master of his realm. A truly unique individual, considered a god by some, Selasie was born Tafari Makonen. He never drank alcohol and worked tirelessly. The King of Kings rose at four every morning to pursue the only thing that had occupied his entire life, his vision for Ethiopia.

When things turned sour in 1974, the year he was deposed by a group of junior military officers known as the Committee or Derg, the Lion of Judah had spent 44 years implementing this vision, and proving his masterly at overcoming obstacles to his power till the bitter end.

Why did Selassie fall? What made his vision for Ethiopia different from the “ Ethiopia First” aspirations of the Derg? The answer is that in his scheme of things, Selassie came before Ethiopia.

If you have read Kapuscinski’s book “ The Emperor” about the last days of Selassie’s rule, the sad truth emerges on how visionary leaders, revolutionaries even, discover too late that their life’s work had been ruined because it was built on their personal ability to control everything.

Inevitably positive reform and personal control became rival beasts that lock horns to bring the system down. Selassie’s body was discovered under the toilet of one of his Palaces in 1992, he had died aged over 80, a man of numerous contradictions.

Ethiopia under Selasie had became a symbol of the progressive African nation, a one time member of the League of Nations and a founder member of the United Nations, Addis Ababa is the city where the first OAU conference was held.

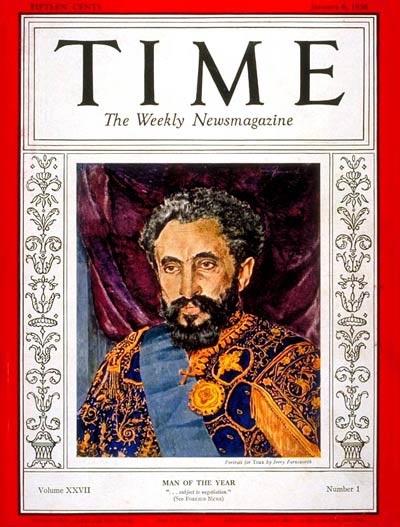

Haile Selassie was hailed by the West as a progressive African leader and an emerging global statesman who guided the country through the difficult years of Italian invasion of 1934, and the Ethiopian resistance on the side of the allied forces during World War 11. In 1936, he graced the cover of Time Magazine, as the man who modernized his country increasing school enrollment, industrial exports and successfully courting foreign aid ($150 million a year) for Ethiopia, a huge chunk of which was spent on “ 35,000-man army, a 29,000 strong police force, an elite palace guard and three separate intelligence services”.

But while seen outside as the man whose vision was leading Ethiopia to greatness, at home Selasie spent his energy at the power chessboard. He played one group against the other, royals against bureaucrats, peasants against landowners, one set of sycophants against another, different security institutions spying against each other and everyone. No one could grow powerful enough to challenge him.

Careers could be built or lost depending on access to Selassie since the “source of wealth was not hard work but extraordinary privilege”. So Ministers he trusted were rewarded even if they were unpopular while those who differed with the King or outshone him were cast out, imprisoned or killed. Frequent cabinet reshuffles meant new comers would forever be indebted to the Emperor while Palace rejects sent the message that loyalty to the emperor was all that mattered.

Corruption, a result of the multiple layers of factionalism all seeking favors from the emperor became the order of the day. Tax authorities pilfered the royal purse, donor aid meant for victims of Ethiopia’s famines disappeared into the pockets of local authorities and government officials, money for ordinary soldiers was stolen by their commanders, the whole nation was one huge looting exercise. Nonetheless, this politics was precisely what kept Selasie in control since it was based on the cardinal principle of loyalty to the King.

Selassie had created a nation of sycophants who eventually told him only that which he wanted to hear. So out of touch was the Emperor from the problems of ordinary people at the end that he was pictured handing out money to crowds of beggars totally unaware that such imperial gestures were irrelevant in a country yearning for reform.

He did not learn until it was too late of the conspiracy by the Derg made up of junior military officers protesting against the corruption in the army where promotions were based on merit but on loyalty and tribe. As the malignancy grew, officials instead of fixing the problems, officials reacted by feeding the nation with a few painkillers and a host of distractions including parties and anniversaries and official rhetoric on development.

Selassie, the 255th monarch of Ethiopia is the pitiful story of a man who worked hard to become a cult figure, a reformer who failed to rely on the institutions he himself had created instead constantly undermined them. He was the embodiment of the truism that absolute power corrupts absolutely as well as the dilemma in many African countries about the extent gifted leaders can hold their countries at ransom for their personal contributions to the development of the nation.

Unfortunately there are abundant examples of how shrewd leadership quickly caricatured into vampire dictatorships that sucked nations dry of initiative and spirit de corps. You could ask the question how far our own President has slipped down that slope to join the Emperor at the club of former deities?

Published by Monitor Publications