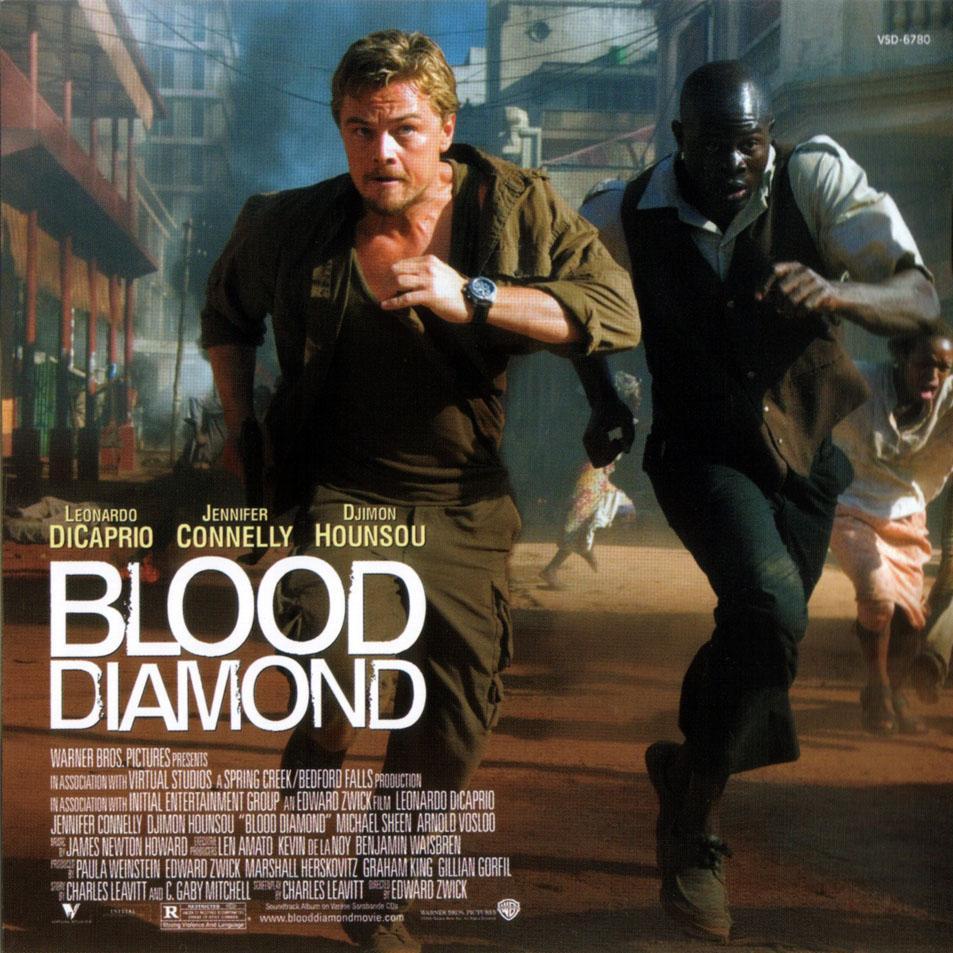

Before the film Blood Diamond was open to the public, a private screening was arranged at the Garden City Cineplex. The cinema was a weekend walk of fame for Kampala’s well to do, a bustling social scene where one could regularly catch faces that were featured in the tabloids. Cinema’s in Kampala tracked beautifully the growing wealth and expectations of the city. After the death of the great Cinemas inherited from the boom times of the 70’s like Odeon, the return to the big screen had been slow. Initially large projectors did the job downtown on strips like Luwum Street that was often the petri-dish for new urban tastes and innovations from fried chicken to forex bureaus. The trading classes here, often Baganda and Muslim, bridged the gap between the developed world and ours through the commerce of everyday things. Leather shoes from turkey, new radios and televisions from Asia, juice blenders and gizmos of every kind.

It was not long before an actual cinema, though small was built on William Street with a spillover bar scene – featuring pool tables and performances and a Club beer sponsorship. It was an immediate fixture on the social scene. It is still amusing how the narrow road – a two-way street transformed into a coveted parking zone for the socialites eager to show off their new motors. This put pressure on the nearby “Pioneer Mall” but also opened the stretch of Kampala Road above it to new businesses such as the Simba group video library run by Patrick Bitature.

This was an exciting time however it was the Garden City location with its functioning escalators and lifts that raised the game. I had run into Don Cheadle , here, when he came to town to promote Hotel Rwanda .

While I did not expect the big stars of Blood Diamond that day as I took up my seat, but the scene was promising. Besides it was my first time for a private screening. While I worked in radio and print where occasional radio swap deals, in which stations would promote a film in return for free tickets for fans and staff had landed me exclusive first looks, they did not compare to this private screening. The affair was an invite only event because a powerful family had reserved the showing. Until then I did not know this was possible for a major box office hit such as Blood Diamond.

My good fortune was a favor extended to me because of a chanced connection that I had with the Ugandan star of movie. In Blood Diamond the husky, hanky bar man with the slightly flirtatious eyes who serves Leonardo Di Caprio’s character (Danny Archer) and his love interest Maddy Bowen ( Jennifer Connelly) was played by Ntare Guma Mwine.

Ntare also happened to be cousins with Simon Mwesiga who in turn was part of my extended circle of true friends. Simon was a complex and passionate character whose pedigree was as near pure blood as one could get with the National Resistance Movement, particularly the now dwindling circle of “historicals” the core team who rolled with Yoweri Museveni from the start. In this case the elder Mwesiga was a personal friend of the President’s dating back to his pre-teenage years. They had also attended secondary school together. This is how at an earlier showing Museveni reportedly made an appearance at the Cinema and congratulated the Mwines. Simon’s father Martin Mwesiga lost his life in Mbale around 1972 in an anti-Amin operation which is mentioned in Museveni’s “Sowing the Mustard Seed”.

In later years I would sometimes wonder about Simon who had an air of romantic fatalism about him, a poet’s intensity and no airs about his famous father. I knew he was close to then Army Commander General Aronda Nyakairima, but he did not speak of these or other relations with the NRM crowd much. We had fierce debates on what sacrifice and heroism meant when outside socializing, he got me and a couple of friends to help him publish a Heroes Magazine with the patronage of some military persons. It must have been controversial to include me as a contributing editor considering that I was also a journalist at the Daily Monitor where some of my articles caused anger and frustration with the establishment. In fact, before the first edition of Heroes Magazine could be printed there was an attempt to hijack it . The first obstacle was by the office of the Political Commissariat of the army as such writing/publishing that dealt with historical contributions of servicemen was considered their domain. Later General Elly Tumwine made a more brazen attempt to take the concept and publish a similar magazine. This attempt fizzled when the whole affair was exposed in the Daily Monitor in a long piece written by Emmanuel Gyezaho. In the world he straddled, projects like his, funded by patronage and other unofficial budgets, much like organizing awards or conferences were cash-cows to get money out of the system and it is possible his magazine idea was seen as something with a potential for repeat business.

I guess Simon was something of a rebel like his father.

In the close-knit world of dangerous subversive activities Mwesiga Senior must have been really close to Museveni. Choosing a life of revolutionary war for many young men in perilous times meant putting one’s life and family in grave danger. There were many funerals. Mwesiga Senior’s death was one of them. Nonetheless the relationships built in the crucible of violence, uncertainty and impermanence have long lasting effects on those who survived. The long-lasting reign of the NRM crowd introduced some of the good, bad and sometimes dangerous instincts into public affairs as power and later the economy became consolidated in the hands of the class that fought the war. So enmeshed was this class of people, with tributaries into government and society, that those of us in the analytical crowd benefited immensely from knowledge of earlier relationships and importantly feuds in interpreting political behavior – something that foreign journalists often missed.

More than often however we were like spectators behind the velvet rope that divided privilege from the rest. Moments like the screening of Blood Diamond helped illuminate that divide. As we listened to one or two speeches, I was as eager for the movie to start but excited that I could see up close these same relationships cradled in a hall that exploited imaginations and blasted cultural conversations as entertainment.

While Simon Mwesiga remained in Uganda and tried to build a career as an entrepreneur and later publisher, his cousin Ntare Mwine, the star of the movie, was raised in America and went on to become an accomplished writer and actor. The cinema hall was packed with folks who I assumed were the close friends, family and associates of the Mwines. Ntare’s father Frank Mwine was famous in the Uganda financial world once running the Uganda Commercial Bank. In some circles he was considered one of the Knight Templars that formed the phalanx of NRM professionals, some returned from exile and others not, who had restored the stabilized the economy. While Ntare got to make a movie that depicted an African country being ransacked by violence and looted for its minerals, a customary trope in Hollywood, complete with a conflicted White Savior, it was in fact his cousin Simon Mwesiga who lived close to military and political figure capable of participating in the sort of dramas, such as the Congo wars that fed the real world context of the silver screen.

Men like Kahinda Otafiire.

This must have been why Blood Diamond, its setting and story was so familiar. It stood out immediately. Seated behind us, for example was the Minister of Finance Dr Ezra Suruma. An elder in the NRM family with socialist instincts he was now in charge of an economy that was beginning to feel global shocks more easily. Uganda was also exporting several minerals, the most famous of all, gold whose sources lay elsewhere in the neighborhood. These were the early days before gold would overtake coffee as Uganda’s leading export. Ugandans grow coffee but gold mining is limited.

[We will write our next episode about the curse of gold in Uganda’s political history including its meteoric rise, without much fanfare, to the position of its leading export]

Unmistakable too was the rotund presence of Gen Kahinda Otafiire. I knew Otafiire from before I became a journalist. The circumstances had to do with his being in charge of the “economic desk” of Uganda’s involvement in the war in Congo. While Blood Diamond was in production, the International Court of Justice had ruled that Ugandan military personnel had participated in the looting of the Congo (DRC) in a case brought about by the Kinshasa authorities. The court found that was not a government policy to encourage the looting and pillaging of DRC’s resources but that it was also indisputable that UPDF officers, some of the “highest rank”, were involved. Subsequently it ruled that as such these officers and their actions were the responsibility of the government of Uganda. Uganda was asked to pay billions to DRC in reparations, money it still owes.

I pondered this bizarre twist. Did Otafiire, Suruma or Hon Ruhakana Rugunda who was also in the crowd draw a dotted line between the pillaging depicted in the movie and the real-world events upon which they are based? Did the South African mercenary force injected itself in the conflict in Blood Diamond seem similar to Executive Outcomes, the British founded military company (many of the significant figures behind it were based in South Africa) that had ties to Uganda? Its founding partner Anthony Leslie Rowland Buckingham or Tony was in 2006 the head of Heritage Oil and Gas and would soon announce oil finds in western Uganda.

Later I heard that the researcher hired to anchor the movie on realistic African events had spent time in Uganda. When covering the events of the war, many of my newsroom colleagues, including some who came from areas in Western Uganda that had seen civilian casualties from groups like the Allied Democratic Forces. At the common working area, I would argue with Joseph Beyanga, Charles Mwanguhya and Frank Nyakairu about the logic of withdrawal of UPDF from the DRC in 2003-4 because I had held on to the view that the military occupation was in Uganda’s national interest, if the alternative was an ungoverned territory. With time I also came to see the “illegal” gold trade similarly arguing that re-export of Congolese gold through Uganda allowed for businessmen in the Congo to purchase Ugandan produce and imported goods. In places were governance was weak, the increasing volume of trade between Uganda and DRC also indicated that there were communities that were functional with needs such as exercise books, medicines, Chinese electronics, salt, sugar and soap. The widening trade, I thought was always cheaper, now that Uganda had no forces in DRC, than military interventions when required. If gold and mineral trade kept these communities engaged with Uganda – I considered it a plus.

I was also perhaps the only one in the newsroom with some direct knowledge of street level dealing of gold, diamonds and that kind of thing as this was unavoidable in the places I hanged out – such as William Street in the second half of the 90’s. This is how I knew of diamond auctions, of Otafiire, and Juma Seiko and others. Even then my view had been tied to the notion that state-building in DRC and South Sudan would require Uganda’s creative involvement.

As we left the theatre ( I had to head back to the newsroom) my colleague reminded me that the price of diamonds was never affected by the nature of the conflict(s) in Africa. Millions could die but the value of the stones traded mostly in Belgium cities like Antwerp would continue.

“ The value of diamonds are likely to be affected by an attack in Antwerp than in Ituri” he argued. As bizarre as our encounter with characters who knew more than the movie showed, that irony would last long before they all died, we decided because “This is Africa or TIA”