Like many significant men and women who have risen to the surface of political society in Uganda in recent times, the late Major General Benon Biraro is an NRM man. The last few times that we met he was promoting the idea of a dialogue between Uganda’s leading political forces – themselves extracts of the Movement.

On one occasion we spoke as guests at a student leadership meeting at Victoria University.

I had scribbled some notes on the fast disappearing sources of public morality which, given the quality of political competition, in which Biraro had been a presidential candidate, was being cannibalized so quickly, that in my mind our society risked waking up on a barren strip, exposed to the elements of whatever is possible when politics has no moral fiber.

It was in fact an extension of my view that violence, in all its forms, in society was a consequence of the failure of politics to guarantee fair treatment of citizens. For some time, I was convinced, as I am now, that justice when present is evidence of the political organization behind a society. It follows that when it is scarce something is wrong with politics. As a legal matter this is more or less settled. Justice is on the run from the institutions charged with her protection. As political forces have gradually consumed both the law courts and the legislature, as politics commands first call on issues that require impartial adjudication, as a political class with money creates its own rules for governing unequal society- both justice and its moral justification is seen less and less. As a social reality the absence of justice is on display every day. The lack of trust in institutions, the cult of selfish accumulation and its celebration as high culture are just the few signs of how severe we have it.

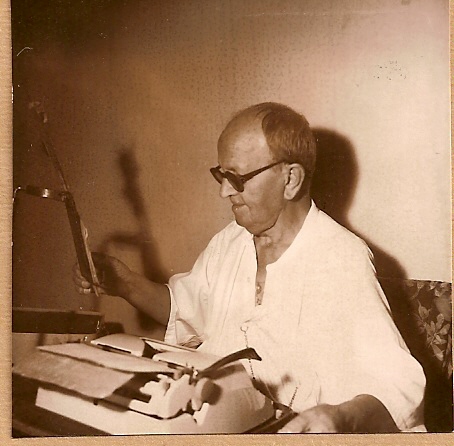

Biraro, in an army general’s physique, spoke after me.

As in his appearances as a presidential candidate one did not find with him the signature of hubris and entitlement so common today with politicians and their agents. The students loved him. He took notes and spoke as someone who was still, like them, and us, on a learning journey. He also left the impression, perhaps because of his military career, that these crises were capable of being overcome, if good people took a stand.

When someone like Benon dies, as he has sadly, the little hopes of calm fortitude against the ugliness of Ugandan politics and its deleterious impact on society expires with it. His life was like the cloud cover that appears in the middle of a heat wave, holding steady and leading to a cool breeze and small showers. It is a reminder that good weather is possible amidst the dust, dirt and heat. That all that perspiration and discomfort of endless sun that saps the energy and spirit and causes deep cynicism to enter the bones of a society like a cancer can be waved aside momentarily because of a man like him speaks the language of hope convincingly.

We shall mourn him and the unfinished work he took on as a passion project after his retirement from the army; righting wrongs with political society while representing farmers – the very class of everyday people for whom bad weather must change. Or else.

One of the ideas he pursued was the notion of dialogue in politics. By this he did not mean political conferences and deals alone. He meant honest conversation by honorable men about what Malcolm X would call the things that are “common” to all of us. He believed once we can agree on what is important – the rest, the arrangements we need to make to embark on a new journey are a matter of course.

In death he raises again the question – where will we find the sources of public morality when, so few exist? Rest in peace.