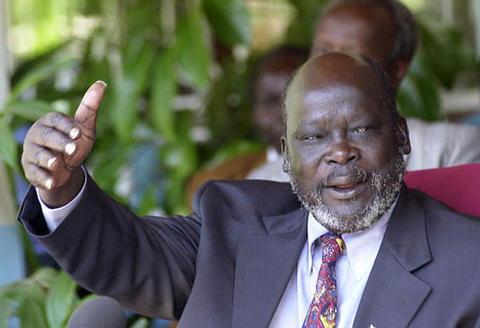

A collection of articles on the challenges facing rebel armies that go on to play political roles- especially after peace accords has recently been published. Titled “From soldiers to politicians. Transforming Rebel Movements after Civil War” it observes that rebel movements that succeed in playing effective political roles- like running a government or being a partner in one- tend to develop political institutions and supporting ideologies during the combat phase of their struggles. In one instance the current weaknesses of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army/Movement led Government of South Sudan are blamed on the earlier stifling of its political institutions by the bullish and autocratic leadership style of the late Dr. John Garang.

Making no real attempt to develop its own vision in the course of the conflict SPLA/M embraced the diverse ideologies of its benefactors- taking money from Marxist movements in Eritrea and Ethiopia and later switching to capitalist and neo-conservative America after the end of the cold war in the 90’s. In comparison movements like the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front or Tigray Peoples Liberation Front- both of which are in power today in Eritrea and Ethiopia were fighting so-called protracted people’s wars; long struggles which relied on managing villages through strong political institutions and attendant ideologies. SPLA/M, its noted may have been clear about its enemies in Khartoum but failed to develop a robust political program for managing Sudan- while its own organs were stunted by personal rule, ethnicity and corruption which continue today. That incomplete transition from soldiering to politics is now an albatross around the neck of SPLA/M having been thrust into government in an internationally brokered North-South peace deal. The Lords Resistance Army was not included but the book makes the point that it is particularly challenging for rebel armies to move from soldiering to dialogue in the course of negotiating peace agreements.

Since peace negotiations between the Ugandan government and LRA backed by SPLA/M begun in Juba in mid 2006, the rebel’s presence at the negotiating table has been weakly articulated as a wider program of representation of Northerners and their marginalization within Uganda’s politics under NRM. The problem is that LRA has never had political institutions, never managed any territory or seriously marketed its creed on the restoration of the biblical Ten Commandments. Joseph Kony instead run a skull society- isolated and tied together by fear. While it had political representatives drawn from the Acholi Diaspora- by contrast LRA has been more effective military organization- strengthened externally by the help it received – and continues to get- from the Islamist government of Omar El Bashir.

In part its political representation at Juba was introduced to make it possible for it to negotiate. Thus one of the major weaknesses of Juba was the distance between the military organization and its political mouth pieces like Martin Ojul and others and by that stretch between the primary pre-occupation that Joseph Kony and Vincent Otti had with reconciliation and reconnecting with Acholi as opposed to the more national claims made on behalf of LRA by Ojul and team. Sources said that while meeting with President Yoweri Museveni in Kampala recently Ojul said he would quit representing the LRA after the episode with the reported brutal purge of Vincent Otti and others. A non-military outsider- Ojul realized that by killing Otti – Kony had distanced himself even further from the only real politics of the peace process- Acholi reconciliation. Moreover Kony’s killing of Otti reminded all of the brutality of the group, the abduction and enslavement of children- the mutilation of their parents- which has denied it wider support over the years.

The answer to the question will LRA/M transform from a military to a truly political movement is increasingly no. This raises some questions and scenarios for the future of the peace process. One is whether after consolidating his hold with the recent purge Kony can negotiate in person when Juba resumes. If he does it could potentially allow the stakeholders in the process to respond more appropriately to the LRA given its mainly military character. Secondly if LRA chooses to remain active one must address under what circumstances it would resume hostilities. The peace process would need to look to strategies to sustain the current peace or in military terms- maintain a ceasefire. Some observers have suggested that recent defections by senior LRA commanders are a sign that the military organization is breaking up. But from a military standpoint what is happening is the reverse. Since the purge of Otti and his confidants drawn from Atiak- Kony now completely controls LRA.

Together absolute command, the removal of older members, children and women- Kony is left with a leaner and more dedicated fighting force which can move around attack and evade attacks. Some of the inconsistencies in the testimony of former LRA commanders like Opiyo Makasi and Sunday Otto even suggest that Kony may be attempting to counter infiltrate his opponent the government and they may still be working for him. One realistic scenario is that if Kony wants to abandon the politically driven process of peace he will probably order an attack on a non-civilian target between now and the resumption of talks- first to boost the morale of his remaining troops but also signal that he is still in business. Thirdly even if Kony has tried to bridge the gap between himself and the Acholi people making it possible for traditional justice to remain a viable exit from the ICC warrants of arrest for him- any final deal with LRA will require the cooperation of its former backers in Khartoum.

Recent problems in Sudan especially the unraveling of the North-South agreement has led Bashir to summon militias allied to his government- like the LRA. Kony may still be paid by Khartoum to pile pressure on GoSS which has recently proved incapable of guaranteeing security in some areas. It is the view of this writer that the most practicable conclusion to Juba is in-country exile for Kony where he and his fighters are relocated to northern Sudan through a deal with the Khartoum authorities. As President Yoweri Museveni meets with other regional leaders and the US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice in Ethiopia today- they may well be advised to extend the Tripartite Plus to include GoSS so as to widen security sharing and cooperation to the SPLA/M.

Ultimately however the transformation of LRA into a political organization may not be immediately possible or even necessary to conclude a peace process. However if he relocates away from the geography of the 20-year conflict it does not mean the political issues that LRA raises should be not be urgently addressed. If the NRM government wants to avoid turning political opposition in Northern Uganda into another military movement it must triple its investment in the reconstruction of the North.