In 2004, together with morning show presenter Christine Mawadri, we were ushered into the waiting area of All Saints Church in Nakasero. Located just next to the city residence of the Ugandan President, the Anglican Church is one of the main places of worship on Kampala’s religiously segregated hills. The office of The Most Reverend Arch Bishop Luke Orombi, then newly enthroned, was located at the back of the old church. Its entrance faces the towering and controversial Hilton Kampala Hotel- whose Ugandan-Sudanese owners are a staple of embezzlement scandals serially played out in the media like “Days of Our Lives”.

The ascension of Orombi to this esteemed place has its own political story. However for over a hundred years religious leaders have bolstered their careers like the politicians they counsel on these hills.

In the late 1850’s the battle lines were drawn between Catholics and Protestants. Before them Muslim merchants battled for influence over the then absolute kings of the Baganda- from which Uganda takes its name. Across the Anglican perch of All Saints church is the shiny golden dome of the Old Kampala Mosque gifted by Gen Idi Amin Dada and recently refurbished with the petro-dollars of the now deceased Libyan leader Muamur Gadaffi.

Now fighting for space with the old Asian quarters the Mosque and its surroundings are some of the oldest surviving buildings in the city today. Below it the old market, bus park and stadium are being swallowed by the march forward of modern commerce that exports prostitution right up to the steps of the Hindu temple- whose moral influence has not been as prominent as the more political-religious establishments around it.

Now fighting for space with the old Asian quarters the Mosque and its surroundings are some of the oldest surviving buildings in the city today. Below it the old market, bus park and stadium are being swallowed by the march forward of modern commerce that exports prostitution right up to the steps of the Hindu temple- whose moral influence has not been as prominent as the more political-religious establishments around it.

The seat of the Buganda Kingdom is scattered in the nearby hills. The Rubaga and Namirembe hills hosting red brick Cathedrals- monuments to bygone days of influence near the court of the great monarchs like Mutesa I in whose reign- blood was spilt here in the name of the true religion.

All Saints is an important diocese because besides being in the capital city many of Kampala’s leading families that have emerged from the recent violent shuffling of the political-deck-of-cards are Anglicans from the west of the country. The reason we had an early morning appointment with the new Bishop was his decision to back runaway American parishes. These parishes had sought a new spiritual home across the Atlantic because of their disagreement over gay marriages and the consecration of an openly gay Bishop, Gene Robinson.

In explaining his actions Bishop Orombi made both religious and political arguments. He said that the 1998 Lambeth conference of the Anglican clergy elite had voted that homosexuality was immoral just like an earlier conference had set out as unbiblical the widespread practice of polygamy in Africa. By turning their backs on the agreement over homosexuality he felt his Anglican brothers had betrayed the African church. This was in essence a type of war for independence- and for moral self-determination by African dioceses.

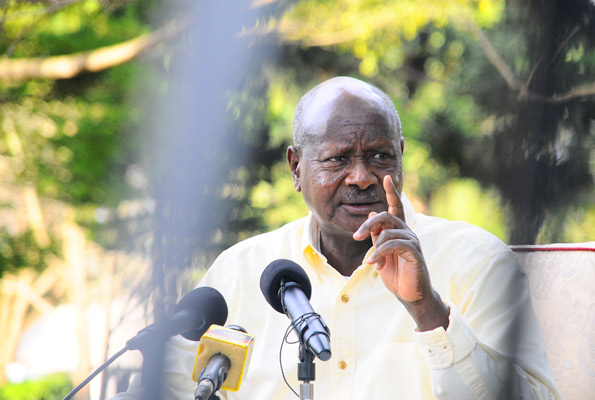

“Our view is that homosexuality is a moral issue and a sin. The Americans do not see it like that. I was with the President [Yoweri Museveni] yesterday and he said HIV/Aids is not only a medical problem, but also a moral one. We can defeat homosexuality just like Aids,” he told us. In addition Orombi referred to administrative pressure from American clergy- threats to withhold church aid-as essentially neo-colonial.

Recently with the emergence into prominence of the so-called “Kill the Gays Bill” that has garnered hundreds of thousands of signatures in an online campaign I was reminded of the constituencies of the debate about gay rights – or any other rights in Uganda. Over the years I have observed a convergence of interests in the conflict. It brings together politicians, priests and activists- much of it over the head of the so-called socio-religious and moral roots of the issue.The tone of the Bishop that the issue of moral choice was being inflicted by powerful external forces did not for example address the moral landscape at home. And not by mistake perhaps.

Uganda after all had produced Idi Amin and Joseph Kibwetere- the man accused of the worst religious mass suicidein recent human history in Kanungu- a largely Anglican area of western Uganda. Then there was the death in office of Bishop Janaani Luwum allegedly killed by Amin- allegedly for meddling in politics. The wars fought here have seen entire generations descend into physical and moral chaos like the internment of millions in internally displaced people’s camps for almost 20 years, the death of thousands in nearby Rwanda whose relatives across the border bore witness if they too were not involved in the fighting. Death, bad government, corruption, family strife has stalked the soul of the country for generations.It therefore appeared if not trivial – then certainly not driven by moral imperative that out of the moral cesspit rose to prominence the issue of same sex relations. There was something more practical too about the protest mounted by Orombi and others.

The idea of giving spiritual sanctuary to American churches gave it a special place in their relationship to western sponsors- since both the religion and a significant portion of the Church’s finances were foreign to begin with. “ We won’t be influenced by money” the Bishop said.

There is a general perversity in the behavior of African elites before a foreign audience. It is as if having a problem to solve in which foreigners are interested is a ticket to some big game, a confirmation that one is part of a broader civilization perhaps. And so the public debate on local issues (like whether the church should consider same-sex issues superior to other crisis) take on a weird quality once placed on a global stage. The story of aid to Africa is strewn with this variety of the exhibitionism of victimhood for foreigners to compete for many times with financial charity- and the industry of support it has generated. It becomes a bidding game for who has responded to the most misery. Or conversely who has the most misery to pawn. Perhaps that is why a moral issue has become a very political one.

When David Bahati, the youthful Mp from Ndorwa West, a rising star in the National Resistance Movement and friend of the religious right in America put forward his Anti-Homosexuality Bill (AHB), we had a lengthy discussion on a radio program and later privately over the foreign policy implications of the law. However am resigned to the view that the AHB like other issues that resonate with a foreign audience (like terrorism, regional military adventures, etc) play to political instincts of the ruling establishment. Many policy debates are chewed up by the hypocrisy of these debates that pay lip service to everything from the “war on terror” to the “war on poverty”, from “trade not aid” to the notion of homosexuality as evil.

In exchange they produce a superficial engagement that occupies public debate and conferences and projects for those involved. Very little about values are exhaustively evaluated by this process.

Many of the twitter supporters of the petition to stop the bill from passing before Christmas for example get the sense that gay people in Uganda are living in an atmosphere that produced that seminal religious event- the Uganda Martyrs in the late 1800’s. However I have also found that local activists have often also exaggerated the day to day risks they face in the face of the interest in this issue- often because aid assistance after the AHB was tabled has been for protection, travel, rent and security.

So now many people involved with the movement to hold off the “Kill the Gays Bill” ask how politics (and its religious arm) will resolve this issue especially after the high profile statements of the Ugandan Speaker, Rebecca Kadaga, who has found political capital in suggesting Mps have a sovereign right pass the law before December 25th.

If the matter comes before Parliament the likelihood is that the law will pass. Most Ugandans are also conservative enough in attitude not to care deeply for its legal consequences. It is unlikely to be signed into law by a Ugandan President however because of the sheer consequences of international reaction. This is so especially for the current Ugandan President who has recently seen the country descend into a pariah status over corruption scandals in his government and accusations over the role of the Uganda government in the Congo crisis (another story). What the debate has served has been to raise the stakes for openly gay behavior-, which may attract social sanction, not necessarily legal ones, since a law against homosexual acts has long been in the old colonial era Penal Code.

The irony of all this is that for a country that has a real values dilemma having witnessed the cannibalization of society by civil wars, vampire regimes, ethnic pogroms and caricatures of social decay in the slums, refugee camps, drug rehab centers etc- we should be playing at having a real conversation about the place of morality in social cohesion and government policy. The AHB debate is almost like debating whether Joseph Kony whose record of evil in the name of religion- is gay. It is not helped by well-meaning but nonetheless ignorant outsiders whose education about the issue as a domestic conflict is as wanting as majority of the Ugandan public who engage with the AHB because of the amount of news coverage it is getting- then go out and happily hold hands or buy local tabloids with university girls kissing each other.

On a side note – I have been meaning to write a piece about Ugandan single mothers – that product of the social and political combustion of the last 40 years but particularly about the generation they will raise. Single motherhood in many ways is the ultimate middle finger to not just patriarchy but traditional political and religious society. The preponderance of single mothers in the work place has also marked the arrival of “women emancipation” which is owed in part to donor-financed reforms in the 90’s- that created a buzz for affirmative action with real social consequences. It is not that single mothers constitute a new liberalism even though taking Bishop Orombi’s choice of moral sin (as targeted at polygamy and homosexuality) they moot new society grounded in self-reliance and therefore personal choices. Perhaps this will eventually set up the stage for a more exhaustive debate by a generation accustomed then to the idea of free choice. For this reason alone the debate on the AHB no matter its outcome is a curtain raiser. Maybe.