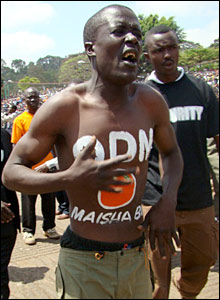

As Kenya stands at the crossroads, caught like an animal in the lights of a speeding truck, some calls for reconciliation, while welcome must take into account some of the stark realities of the current situation.

Considering the losses in the Parliamentary elections of President Mwai Kibaki’s party and his controversial declaration as President- any negotiated deal to keep him at the helm may inadvertently groom a strong arm President who has shown his capacity for closet dictatorship.

This is because administrations lacking popular legitimacy often turn to the instruments of coercion, like the intelligence services, the police and the army not just to maintain power but push government programs.

So far- Mwai Kibaki has shown he can use force to aid his political agenda, peeling press freedoms and ordering troops to shoot looters and protestors on sight. As a political operator- Kibaki no doubt appears to understand the statement “possession is nine tenths of the law”, immediately seizing the opportunity to legitimize his narrow victory by swearing himself in. He can now rely on support of his Kikuyu constituency and the instruments of state power to put up a strong negotiating position.

If he remains a Kikuyu President as opposed to a Kenyan President, Kibaki will shore his vulnerability with force. It is important that any political arrangements avoid a strongman in Kenyan politics since this will not only hurt the democratic tradition but has severe implications for internal as well as regional security.

Kenya’s partners including countries like the United States and Britain should not approve of an illegitimate win for Kibaki nor for the sake of immediate peace support a Presidency in a political alliance where power is still concentrated on politically weak Executive.

Those who are brokering a deal between Kibaki and his challenger, Raila Odinga are therefore faced with a difficult balancing act.

One preferred scenario is the strengthening of Parliamentary power, perhaps using it (through an agreement of both sides) to create an Executive Prime Minister- a position where Raila can conduct the business of government.

Kibaki has rejected this option before- but the current circumstances must be used to convince him that the other route is one of considerable hardship.

If Kenya descends into a “police state” it will have several repercussions.

emiller@iafrica.com

Jakaya Kikwete

One is the isolation of Tanzania within East Africa as the situation in Kenya begins to resemble that of other countries in the region particularly Uganda where in 2006 a closely contested election produced an ambiguous result (with ballot rigging and delayed announcement of the results) which has robbed President Museveni of popular legitimacy.

Ugandan government has unsurprisingly relied on force, riot police, intimidation of political opponents and a clampdown on freedom of speech- all instruments of coercion that have become the inevitable retreat of failing legitimacy.

Tanzania, which while it has a monolithic system, considers itself as largely civil and democratic will find few friends in the region, already distancing itself from the proposed East African Federation over similar concerns of “democracy”.

Additionally, a potential police state at the borders of Uganda is a blow to Kampala’s own progress toward “democratization”. Uganda in the last two decade has no qualms dealing with security issues which have been at the center of the state and may see itself as able to do business with a Kibaki presidency which mirrors its own power politics.

However surrounded by uncertainty including serious security risks from Burundi, Rwanda, DRC, and Sudan- Uganda’s priorities will remain in the security sector as the country rolls towards another difficult re-election bid by President Yoweri Museveni in 2011.