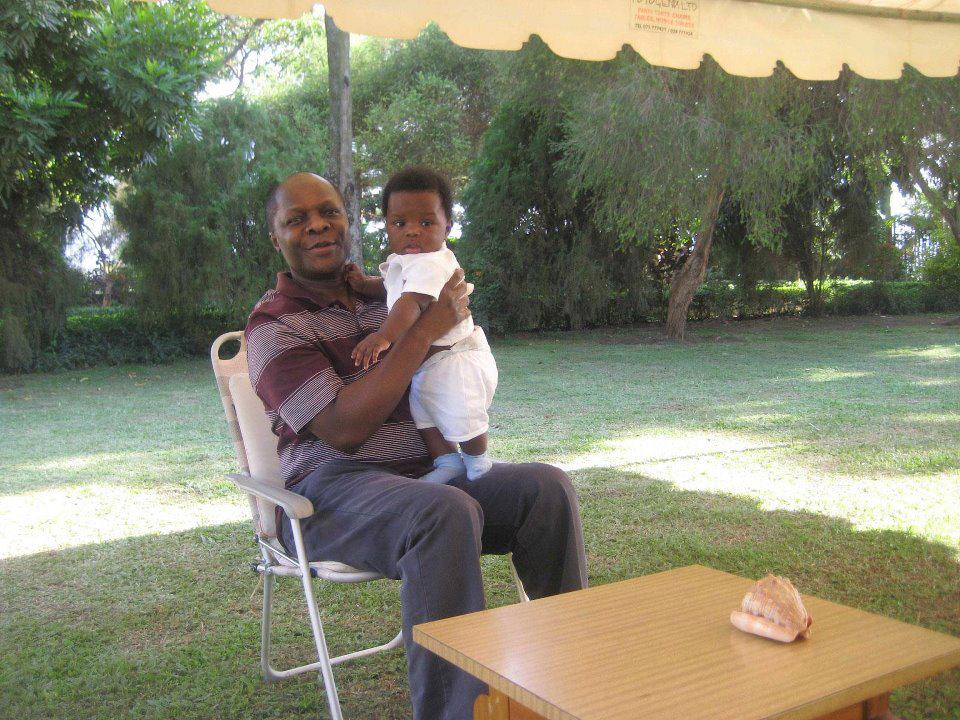

In December, my mother told me after a 4-year wait to have power extended to her retirement home in one of Uganda’s western towns, she had been asked by officials of Umeme, the power distributor, to buy her own “transformer”. This is because where her house is, according to the same guys was removed from other residences so much so that she could not be supplied at cost. The local evaluation officer with whom she had done the four year bureaucratic dance which involved hiring her own surveyors and numerous unofficial charges that involve this kind of quest eventually travelled to Kampala. At her request, I accompanied him to Umeme’s headquarters opposite the New Vision newspaper, to make her case to another official. Why I asked this man, who claimed he had shown my mother as much kindness as she had shown patience all these years, was the old woman being asked to buy her own transformer? Does it mean it would serve only her? How can she own a stake in a public utility?

“ If she wants power there is no other way,” he responded. “What about the Rural Electrification project,” I asked. I could vaguely recall covering such a thing years ago. What had they done?

These interactions with officialdom often strike me as surreal. Often my real distance to the issues is microphone length, or laptop close or pen and notebook cozy. It is a fragment of my journalistic and intellectual pursuits. True as a good son my mother – who probably thought company officials- may be partial to her son a “big shot” journalist and muckraker- may have been onto something here. Social capital is essential to competition for public services. But being ridiculously close to policy “failures”can quickly add to one’s appreciation of the stakes.

Just weeks before I, and several other talking heads, had been invited by the Electricity Regulatory Agency to a “roundtable luncheon for top executives and representatives of key trade organizations at the Kampala Serena Hotel to discuss current developments in the electricity sector and the measures being considered to address the current power supply and financing situation”.

I took it seriously and went to make two cases that I scribbled in my notebook. They are the products of the last 8 years of covering the energy and now the oil/mineral sectors. One argument was that instead of abolishing the electricity subsidy (this meeting was one of the motions towards this goal), that the government re-directs it to rehabilitating the electricity grid. Major losses from the grid had been scaled back but I did not see private investment being a good replacement for public money to air-out the grid, which is most congested in Kampala, Wakiso and Entebbe. Cutting down these losses are a major source of immediate savings for available power which, was in short and expensive supply.

A second argument was that government policy dedicate itself urgently to generating electricity from Uganda’s crude oil. Having been an opponent of the investment that Uganda made in so-called “emergency power” during the shortages of 2005 when containerized generators were procured, I had spent considerable time understudying and promoting Heavy Oil Generators. This effort, Uganda’s procurement nightmare notwithstanding, was beginning to pay off. Countless hours spent with officials from the Ministry of Energy, Finance and my Think Tank buddies making these two propositions did not, I felt, mean I could not make the same argument to this industry group.

The whole affair went like most luncheons do.

I took notes – and was at one point mildly reprimanded for my enthusiasm by the Board Chair of ERA- Richard Apire- when I veered to discussing what electricity provision meant in terms of the country’s social compact. Another pillar of Uganda’s energy policy that I wanted to debunk is the tyranny of big projects.

Bujagali this and Karuma that.

In fact looking at electricity consumption today, a significant portion is from small, off-the-main grid generators (We were lucky that heavy rains helped generate some 40MW from dams like Ishasha by Christmas). It goes without saying that under-investment in energy infrastructure is more than an inconvenience to mothers and sons. Months later Umeme protests broke out so that is that. What is rather disturbing is how much more serious the energy shortage is.

An argument has been made, along with some misguided tongue lashing of Uganda’s intellectual class, by my friend Andrew Mwenda about how the electricity policy is an urban and middle-class fix. In fact another way to look at electricity shortage, the stunted grid, and the inconveniences to customers, is to calculate the full cost of not having cheap sources of power. Uganda has millions of boarding school pupils and students who consume tones of wood fuel every year. Add to this the army, police, prisons and other institutions. Its growing populations and rapidly urbanizing countryside is doing so in conditions where cooking fuel is basically wood fuel. The stresses on land for trees and farming are now a common source of conflict as pastoral and cultivating communities eat into gazetted forest and so forth.

The vision of the Rural Electrification Agency of complete coverage by 2035 is laughable under these conditions not just because of its own underwhelming record (my mother is witness or victim) but because by then the crisis would have come full circle. The cost of not having alternative power can be calculated by looking at the cost of repairing the tree cover, attending to conflicts related to climate change, and other associated nightmare scenarios including water shortages et al. It is not just the short-term business cycle that is suffering.

One challenge for energy policy that is not being discussed is how it is critical to human security- in helping Uganda avert the seemingly ever present danger of environmental disaster posed by a changing climate. This goes beyond the argument about middle-class comforts etc.

Maybe I should end this post by saying that at the end of 2010 negotiations with a Norwegian firm for generation of electricity from Uganda’s crude oil had collapsed. Ugandans need to seriously activate cheap power from local oil sources urgently if only to buy time for large projects to come online. Also under-served populations would benefit from a focus on smaller sources while the government can do itself a favor by investing in a clear and rational grid. Maybe then someone else’s mother will not be asked to buy a transformer.