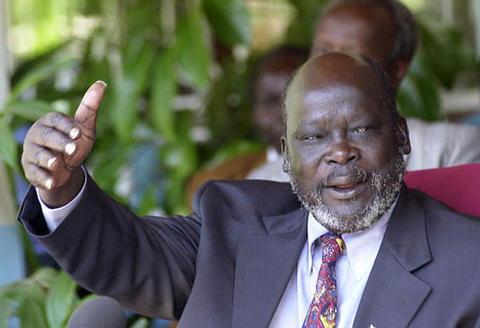

Here are Olara Otunnu’s comments on international justice upon receiving the Havard Law School Association Award. So heartbreaking that this fine mind, one of the best Uganda has ever produced should remain out of the country. Mr Otunnu is viewed as a political opponent by the Ugandan government.

Olara Otunnu

A remarkable evolution has taken place since I was in the Law School. An impressive body of international instruments and norms has been developed and has gained universal acceptance.

We now have in place what I call a ‘ community of values’, covering a broad spectrum of concerns, including human rights across the board, democratic practice, environmental ethics, the rights of women, and the protection of vulnerable populations in times of war.

But, alas, we are not yet in a position to declare victory and go home. I remain deeply preoccupied by a cruel dichotomy, this wide chasm that persists between agreed international standards and impunity unfolding on the ground.

The era of application

To overcome this gulf, we need a systematic campaign for the ‘era of application’ – – for transforming international instruments and standards into facts on the ground. To my mind, the time has come for the international community to redirect its energies, from the normative task of the development of standards and rules, to the compliance mission of ensuring their application on the ground. In particular, the ‘era of application’ needs to be embedded within formal, structured and binding compliance mechanisms.

And I spent my last years at the UN, working to crack this conundrum, in the specific context of protecting children exposed to war. After working to put in place, over several years, a comprehensive body of instruments and norms, in January 2005, I put forward a detailed action plan, proposing a structure and a series of measures necessary for a formal compliance mechanism.

After almost six months of intensive negotiations, the Security Council, in a groundbreaking development, unanimously adopted Resolution 1612 (2005) on July 26, endorsing the structure and the far-reaching measures contained in my action plan.

This marked a turning point of great consequence. For the first time, the UN had established a formal, structured and detailed compliance mechanism of this kind.

Those who brutalize children and deny them education and medical care in situations of war, are committing two crimes simultaneously — they are destroying the present as well as the future.

Those who brutalize children and deny them education and medical care in situations of war, are committing two crimes simultaneously — they are destroying the present as well as the future.

These violators need to be identified, named and held accountable by the international community. The compliance mechanism contained in Resolution 1612 (2005) is designed to do just that , and it breaks new ground in several significant respects.

First, it establishes a ‘from-the-ground-up’ monitoring and reporting system, which is tasked with gathering objective, specific, and timely information–‘the who, where and what’–on grave violations being committed against children in situations of armed conflict. UN-led task forces in conflict-affected countries are to focus on monitoring the following six major crimes against children: killing or maiming; the recruitment or abduction of children for use as soldiers; rape and other sexual violence against children; attacks against schools or hospitals; and the denial of humanitarian access to children. These six crimes were especially selected because of their gravity, because they are specifically proscribed under relevant international instruments , and because they are ‘monitorable’.

Under this new mechanism, UN-led task forces are being established, ultimately covering all conflict situations of concern, to monitor the conduct of all parties, and to transmit regular reports to a central task force based at the UN headquarters in New York. Significantly, these reports are designed to serve specifically as ‘triggers for action’ against the offending parties.

Second, all offending parties, governments as well as insurgents, are to be identified publicly in a ‘naming and shaming’ list. The last report I prepared (2005), for example, listed 54 offending parties in 11 countries. These included: the LTTE (Tamil Tigers) in Sri Lanka; the FARC in Colombia; the Janjaweed in Sudan; the Communist Party of Nepal; the Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda; the Karen National Liberation Army in Myanmar; and government forces in the DRC, Myanmar and Uganda. The latest report (2006), compiled by my successor, lists 40 parties in 12 countries.

Third, the Security Council has ordered offending parties, working with UN Country teams, immediately to prepare and implement very specific action plans and deadlines for ending violations for which they have been cited. Typically these should include: immediate end to violations by the listed party; undertaking by the listed party to the unconditional release of all children within its ranks, within a time-frame agreed with the UN team; time-bound plans and benchmarks for monitoring progress and compliance, agreed with the UN team; and agreed arrangements for access by the UN team for monitoring and verification of the action plan.

Fourth, where parties fail to stop their violations against children, the Security Council is to consider targeted measures against those parties and their leaders, such as travel restrictions and denial of visas, imposition of arms embargoes and bans on military assistance, and restriction on the flow of financial resources. We know from experience that the imposition of carefully calibrated and targeted measures can have a significant impact on governments as well as insurgents.

And, finally, in order to monitor compliance with Resolution 1612, the Security Council has established its own special Working Group, composed of all 15 members, to review reports and action plans, and consider targeted measures against offending parties, where insufficient or no progress has been made.

At the broader level, the establishment of the International Criminal Court (ICC) represents a watershed for the ‘era of application’. After all, it was not so long ago that the very idea was dismissed as a utopian dream of soft-headed idealists. Now that the ICC is in place, it needs to move quickly to establish its credibility as an independent and impartial institution. It must be seen to robustly pursue major war criminals, without regard to their status or political affiliations. In particular, it is critical that ICC accountability not be reserved only for the weak, the friendless, and the fallen.

Harnessing networks of global interdependence

Globalization comes with considerable ‘soft power’. In addition to developing and applying formal compliance mechanisms, in a globalizing world, we can and should harness this ‘soft power’ to promote accountability and the ‘era of application’.

In a world that has become so inextricably interdependent, no entity or actor operates as an island unto itself. The viability and success of various political, economic and military projects depend crucially on networks of cooperation and goodwill that link them to the outside world- – to their immediate neighborhood as well as to the wider international community.

In this context, the force of national and international public opinion; the search for acceptability and legitimacy at national and international levels; trade and financial flows; the growing strength and vigilance of international and national civil societies; and media exposure – – all of these represent powerful conditions and levers to influence the conduct of entities and actors around the globe.

We need to press to full advantage these networks of interdependence (notwithstanding the fact that some aspects of this same phenomenon are of course being exploited for illicit and deleterious transnational activities), by vigorously engaging them in support of international legality.

Without the rule of law, there is no good government, there is no democratic accountability, there is no justice and equality before the law, there are little prospects for free and fair elections, and conflicts that should be mediated peacefully (through normal democratic and legal processes), evolve into violence, if not outright war. Without the rule of law, it is easy to build an infrastructure of repression disguised under various forms, it is easy to massively divert resources meant for education, healthcare and roads, thus condemning large populations to a life of permanent poverty and indignities. Without accountability, corruption and impunity take root and flourish. And corruption, like cancer, corrodes and distorts everything in its path, making development and genuine democratic practice virtually impossible.

These and more are the cost to a society, when there is no overarching and binding structure of democratic and legal accountability.

In this very season, we are witnessed citizens in Pakistan stand up to be counted. They are marching, protesting the removal of their Chief Justice; they are demanding the rule of law, and a genuine democratic dispensation.

In March, in an unprecedented development, the entire judiciary in Uganda went on strike for a week, to protest government impunity and assault on the rule of law ; this, against the backdrop of the storming of the courts by armed troops; ministers publicly threatening and insulting judges; defendants released on bail only to be kidnapped by the army; the proliferation of secret torture centers, which are euphemistically called ‘safe houses’; galloping corruption at the very center of the state; and an era of 20 years of one-man one- party rule.

Incidentally, these two governments – – in Pakistan and Uganda – – have something in common. They are both beneficiaries of a ‘special relationship’ – – they both benefit disproportionately from the political sponsorship and financial largesse of key western democratic governments. I ask: Can the citizens of western democracies stand by and accept this kind of alliance against the rule of law and democracy, this subversion of the very values that underpin their own system of governance?

In the ‘era of application’ can we remain indifferent to this perverse practice of shielding undemocratic and repressive regimes from the sanction of their own people, through the intermediary of external protection and patronage?

If we cannot support those fighting for their rights, at least we should not align against them.

Genocide and crimes against humanity

We are in the 21st century. There is much to celebrate, because in the modern era our civilization has achieved breath-taking advances in virtually every field of human endeavor.

And yet, these quantum leaps in human progress coexist uneasily with a darker side to our civilization. Witness our capacity to inflict and tolerate injustice, our capacity for deep hatred and cruelty towards our fellow human beings. See the way in which we can destroy entire communities in the quest for power, or in the name of ethnicity, religion or race. And yet we had dared to think that these episodes belonged to a much darker era, long consigned to history. Not so. Herein lies my fourth preoccupation.

As we meet here, the children and women of Darfur, for example, are being subjected to systematic ethnic cleansing, rape, massacres and forced displacement. They are crying out for international protection.

It is a wonderful thing that international public opinion is now very well informed and fully mobilized on Darfur. This is unprecedented. Yet this is not enough. This worldwide mobilization must now lead to concrete measures by the African Union and the United Nations, to bring a definitive end to the abominations that are continuing on the ground.

Not far from Darfur, in fact in the same valley of the Nile, is another catastrophe , far longer in duration and unprecedented in magnitude , but with which many of you may be much less familiar .

In northern Uganda, for over ten years, two million people have been brutally uprooted and herded, like animals, by their government, into some 200 concentration camps. They have been forced to live in abominable conditions, defined by staggering levels of squalor, disease, starvation and death.

In these concentration camps, 1,500 people (1,000 of them children) have been dying weekly; this is more than three times the death rate in Darfur. HIV/AIDS is being used by the government as a deliberate weapon of mass destruction; soldiers are screened and those who have tested HIV-positive are especially deployed to the north, with the mission of wreaking maximum havoc on local girls and women. Consequently, the rate of HIV infection in the region has exploded from near zero to staggering levels of 40-60 percent (the nationwide infection rate is 6.4 percent). Imagine 4,000 people sharing a public latrine; women waiting in line for more than 12 hours to fill a jerry can at a water point; and a family of 10 people packing themselves sardine-like into tiny huts of 1.5 meter radius!

The deadly conditions imposed on the camp populations by the government is exactly what the Genocide Convention classifies as, “Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part”.

Two generations of children have been deprived of all education as a matter of policy; they have been deliberately condemned to a life of darkness and ignorance, deprived of all hope and opportunity. The entire mass of livestock of the community was forcibly confiscated, and now their land is being taken as well. And these dark deeds are underpinned by a toxic campaign of ethnic racism, hatred and demonisation, very much reminiscent of other episodes of genocide in the modern era .

The Central Luo society is renowned for its deep-rooted and rich civilization, values system and family structure – – these have all been destroyed under the conditions imposed in the concentration camps over the last fifteen years. This loss is colossal and virtually irreparable; it signals the death of a people and their culture.

So, an entire society – – the Central Luo – – has been systematically destroyed – – physically, culturally, emotionally, socially and economically – – in full view of the international community. A once vibrant and dynamic society has been reduced to a mere existential shadow of itself.

I know of no recent or present situation where all the elements that constitute genocide under the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948) have been brought together in such a chillingly comprehensive manner, as in northern Uganda today. This is what prompted the Ugandan writer, Elias Biryabarema, after visiting the concentration camps, to write: “Not a single explanation on earth can justify the sickening human catastrophe, the degradation, desolation and the horrors killing off generation after generation. Frankly, it’s not entirely imprecise to describe what I saw as a slow extinction – – shocking cruelty and death stalking a people by the minute, by the hour, by the day. [Yoweri] Museveni owes these children, these women an answer: they deserved it yesterday, they do today and will tomorrow.”

The population of northern Uganda has been rendered totally vulnerable; they are trapped between the genocide, atrocities and humiliations that are being systematically committed by the government, and the gruesome violence (abduction of children, massacres, and maiming of civilians) of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). The government has cynically manipulated LRA’s presence and activities to divert attention from and conceal the genocide and the concentration camps. A carefully scripted narrative has been promoted, according to which the catastrophe in northern Uganda begins with the LRA and will end with their demise. This contrived one-dimensional storyline has not only been ‘bought’ but is being eagerly amplified by the international community.

In September 2005, world leaders adopted the declaration on “Responsibility to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity”. They made a solemn commitment to act together to protect populations exposed to such existential threats, when their own government is unable or unwilling to protect them, or, worse, when the state itself is the instrument of a genocidal project. This has been precisely the situation in northern Uganda for the last twenty years.

The genocide in northern Uganda presents a most burning test case for “Responsibility to Protect”.

Will the international community apply “Responsibility to Protect” objectively and non-politically, based on the facts and the gravity of the situation on the ground, or will action or inaction be determined once again by political considerations and targets of convenience?

The nightmare and staggering facts about the genocide in Uganda are well known to embassies, UN agencies, international NGOs, and human rights organizations. Yet, with precious few exceptions, those in a position to raise their voices have instead chosen to join in a conspiracy of silence.

In the face of genocide of this magnitude, where are the human rights activists? Why are there no demonstrations in our capitals and on our campuses?

Where are independent and investigative journalists? Where are the congregations of faith? Where are the people of God when we need them most? Where are the democratic parliamentarians – – members of the U.S Congress, the British Parliament, the Pan-African Parliament, the European Parliament? Where is the voice of the Black Congressional Caucus on this genocide?

When faced with genocide, we have a moral and legal obligation to expose it, denounce it, and stop it, regardless of the ethnicity or political affiliation of the population being destroyed.

The genocide in northern Uganda is occurring on our collective watch.

My last preoccupation is this. In the ‘era of application’, we must strive for the path of a much more principled and consistent application of international norms, particularly concerning human rights, democracy, the rule of law, and protection from genocide. If we do not commit to the same set of standards for all peoples, we puncture the credibility of our normative discourse, and undermine the universality which is the foundation of the new ‘community of values’. When the selective application of these standards become a normal and entrenched practice, as is sadly the case today, then we reap a whirlwind of cynicism. But this state of affairs is neither inevitable nor acceptable. I believe that we have a common responsibility to work to reverse this situation.

Mr. Otunnu served as the UN Under-Secretary General and Special Representative for Children and Armed Conflict from 1998 to 2005. This article is adopted from his speech

on receiving the Harvard Law School Association Award