Rather belated but in my view useful take on the future of Uganda’s opposition movement and some of the challenges they face. Find the original published here. Many thanks to the RAS blog. Article

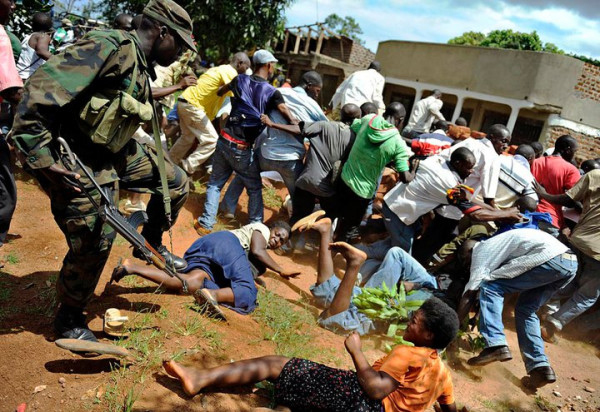

There is a reason why Uganda is one of the most researched countries in Africa. Once dubbed by Winston Churchill as the ‘Pearl of Africa’, the country may well be a graphic novelist’s dream of Africa’s post-colonial narrative. In the last 50 years, this piece of Her Majesty’s former estate in Africa has produced, in broad strokes, both lessons of hope and despair. In its darker episodes, ogres like the dictator Idi Amin – a British trained soldier and cook -have milled with latter day devils such as Joseph Kony, leader of the hopelessly named Lord’s Resistance Army. Civil war, HIV/Aids and grand corruption have held steady here, but so have such globally acclaimed reversals of its failed state status in the late 1990’s. Much of Uganda’s history of recovery has happened under its leader for the last 25 years -Yoweri Kaguta Museveni. A discussion on the future of opposition politics in Uganda is thus a discussion of his career. After taking power in 1986, Museveni restored common security, stabilized the economy, and showed early leadership in fighting HIV/Aids. After a long spell of single party rule he returned the country to multi-party competition. He is also considered crucial to the wider security of the region – a key Western ally in the ‘War on Terror’. Recently critics point out that the bane of the African Big Man; better captured in the words of Harvey Dent from theDark Knight “you either die (read leave power early) a hero or you live long enough to see yourself become the villain” have come true for Museveni. In April and May a spate of brutal repression of popular protests against high fuel prices, which occurred in the shadow of Tahrir Square, turned parts of Kampala into a war zone. Scenes of battle tanks and elite forces confronting unarmed civilians with live fire have led some to compare him to Idi Amin, a charge he shrugs off.

Laws restricting freedom of expression and association, while applied selectively, have turned Uganda into a virtual “North Korea” in East Africa. Mr. Museveni, who lifted Presidential Term limits in 2005, now proposes amending the constitution to further remove the cardinal presumption of innocence for offences like rioting and treason. His detractors say he wants a free hand to ‘rule by law’, silence dissent and possibly even remove age limits in the constitution this time round, so he can rule longer. Mr. Museveni however remains a popular figure whose supporters, both at home and abroad, like to argue has no alternative in the country. Opposition politics is saddled with the additional burden of having to respond not just to how a democratic transition will occur, but how it will figure in a succession to Museveni. In this discussion it is important to note a couple of points. Firstly, that political competition is not a-historical. If Mr. Museveni appears vulnerable today it is not because of his weaknesses but his successes. Uganda has one of the youngest and fastest growing populations in the world, is a trade hub in Central Africa, and is soon to join the club of oil producing states. State-building here has come in the form of a vast patronage network which has helped Mr. Museveni maintain support, but also hoisted a huge albatross of a bloated public sector on him. As seen from the ‘Walk to Work’ protests, while traditional opposition to Museveni has been ethnic, urban fragility is emerging as the new form of state fragility and is the result of the last two decades of patronage politics. The longer his tenure, the more unwieldy the state has become, a result of spending for political support and not development. These problems will continue regardless of how or when he leaves power, and will also form a part of political competition overall. The second issue in appraising Uganda’s opposition is democracy itself. In the first 3 decades of independence, African elites that accepted the colonial structures of the state they inherited competed violently for its control. Lately they have embraced the tenets of democracy – particularly elections – which have become the main source of regime legitimacy. This has created a death match between Opposition parties, including the Ugandan cohort, and ruling parties focused on the interpretation of the ballot. Elections today have become the single most destabilizing event in Africa for this reason. But it has also meant that Opposition politics in Uganda and elsewhere is regime change by another name, not with guns of yesteryears but through the ballot box – hardly a high-minded game dedicated to persuading voters on the basis of a common and shared future. Unsurprisingly, even if the conditions of the electorate – as noted with the fast rising urban underclass that have been crucial in the Egyptian, Tunisian and Libyan iterations of popular change – ballot battles have not tapped into common issues like the state of public goods and services. Uprooting Mr. Museveni through elections has defined Uganda’s opposition and certainly limited its imagination. The Walk to Work protests, which originated within civil society, injected a freshly imagined appeal to change or transformation outside elections, and happened in spite of the Opposition. Ironically, the involvement of the Opposition – especially Dr. Kiiza Besigye – has returned it to the realm of regime change politics and curtailed its impact. During the 2011 Campaign, the formal opposition was fractious, and badly organized. They ran a campaign based on the map of competition in previous elections when a protest vote against Museveni in the non-Bantu north of the country could be relied upon. The campaign also assumed Mr. Museveni, who had been losing the vote by 10% points since 1996, (when he won by over 70 percent,) would use the security forces in unabashed rigging that would render the vote illegitimate and perhaps force a government of national unity. Instead he changed tact, going on a charm offensive with sacks of cash – catching his opponents unawares. Until Walk to Work breathed new life the Opposition it looked finished after a resounding defeat at the polls. But even this effort now looks to be over precisely because the involvement of Dr. Kiiza Besigye in the campaign. Mr. Museveni’s nemesis has reframed what would have been a people-centered, issue driven protest for reforms, as an extension of the regime change politics of the election which had passed. The Ugandan opposition still sees change as something to be obtained through crisis – especially around elections. Their opponents see preventing crisis as crucial. The brutalization of the opposition was ironically a response to the Opposition and not the conditions that activists raised – namely the oppressive economic problems, which reflected in global terms the delayed impact of the financial crisis on African countries. If change comes, it is likely to eclipse the present formulation of political competition as it now is. Museveni’s party and its opponents are not different after all. Both suffer the tyranny of personality. Museveni may be accused of hanging on to the state and his party but he has faced the same opponent over 15 years. This appears unlikely to change. If the urgency of reform caused by the changing demographic, systemic pressures from the economy, a young population and technology are forcing the hand of the Ugandan government today, the NRM and not the Opposition have shown an ability to adapt faster. As the ex-Deputy president of the Forum for Democratic Change and former leader of the Opposition in Parliament Morris Ogenga Latigo once told me, change in Uganda will come from the “cumulative error” of the NRM/Museveni and not necessarily the leadership of the opposition movement. Angelo Izama is a Ugandan journalist, writer and founder of the human security Think Tank, Fanaka Kwawote based in Kampala. He is presently a Knight Fellow at Stanford University.