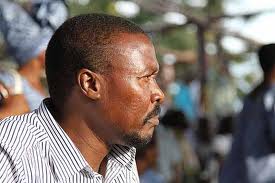

Just 57 years of age, Meles Zenawi, a polarizing Ethiopian prime Minister, reformer and intellectual is dead. Now Ethiopia is going through an unusual but increasingly common political transition, that of death in office. Ghana’s Atta Mills died just weeks ago. Before that was Bingu Wa Mutharika of Malawi. In Guinea Bissau Malam Bacai Sanha died in Paris. It seems to have begun in Africa’s largest democracy, Nigeria when President Umaru Musa Yaradua died, again after a spell in a hospital, in exile. It is possible, in this period of a bitter harvest for death, that many other leaders and their followers are wondering, maybe with reason, who is next? But death as an instrument of political succession and maybe even transition appears not to be as unpredictable and fearful anymore. In the late 60’s and 70’s death of leaders and the attending battles to succeed them were markedly more bloody. Leaders did not pass away with family and friends in faraway hospitals only to return to a state funeral and a process of “handover” of power. Then power was wrested often by killing the power holder or exiling them, by force.

In Uganda, the two towering post independence figures of Milton Obote and Idi Amin all died ( of old age) abroad. Both had been driven out of office through violence. If any thing we are learning today by these mortality transitions, even precarious ones like Togo and Malawi, is that African political systems are healthier today than 30 years ago. Contestations over power are perhaps less likely to end up in complete violence and protracted civil wars. Unconstitutional changes in government are not just frowned upon but could lead to successors paying the high price of isolation and sanctions. So much perhaps that when death, written in most constitutions, intervenes, political elites opt for less disruptive arrangements. While less favored than a political handover that comes as a result of an election, death in office, is not a bad stress test for the stability of political systems. And while it may not overhaul the power of entrenched elites associated with a particular type of objectionable rule, it ushers in new expectations and realligns political forces. Moreover as a generational question, and now with examples everywhere from the south to the north of the continent, the old question of perpetual presidency must be looked at carefully by less emphasis on the sitting president but on those who sit with him and beside him.

In my Ma’adi culture, death has two occasions. When it is painful, such as when a youngster is cut down in his youth and when it is joyful, like when a grand old man or woman passes away in their sleep after a long and fruitful life. As African democracies mature the death of presidents will be less feared or painful but perhaps like Ghana, because our mortality is inevitable, it becomes something to be celebrated, as a legacy, and a door to a more hopeful future.